Residents and landowners around the proposed San Benito

Foothills heard more details about the U.S. Fish and Wildlife

Service’s idea for voluntary easements on nearly 900,000 acres

throughout California

– including southern San Benito County – during a two-hour

presentation Thursday in the Veterans Memorial Building.

Residents and landowners around the proposed San Benito Foothills heard more details about the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s idea for voluntary easements on nearly 900,000 acres throughout California – including southern San Benito County – during a two-hour presentation Thursday in the Veterans Memorial Building.

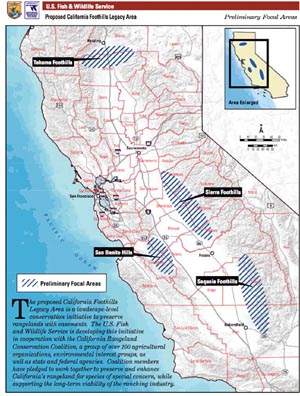

The California Foothills Legacy Area is an easement proposal aimed at protecting the foothills’ agricultural activities and endangered species, while preventing future development. The proposal deems 3.4 million acres statewide – and close to 500,000 acres locally – as crucial habitat for nearly 200 endangered or threatened species.

Local residents filled the upstairs room in the Veterans Memorial Building. Each wall in the room had a detailed map, listing the landowners affected, and showed the local boundary bleeding into Fresno, Merced and Monterey counties. The majority of the plan, though, runs through central and southern San Benito County.

Most of those in attendance expressed negative feelings toward the project.

Rancher Jane Wooster was one of the more outspoken members. Reading from a prepared statement, Wooster called the project a death to local farmers, stripping away their land rights.

“This is like a gut shot,” she said.

Wooster added that she asked her son about the idea of conservation easements and he made good points, she said.

“He said it was a good thing this ranch wasn’t put in an environmental easement 100 years ago or we wouldn’t have electricity, or a telephone, or the Internet, or a well, or a pump or additional pipelines or many other things …” she said. “I can also add our ranch wouldn’t be home to a federal aviation agency site that guides commercial aircrafts or the space shuttle. And I challenge anybody in this room that thinks they can anticipate that when they are thinking about perpetuity.”

Wooster said cattlemen are protecting the area just fine without the help of the government.

“I would like to know where it is written that Fish and Wildlife thinks they can do any better,” she said, “and where it is written that these current operators have current plans to change their operation to the determents of the species.”

But Collette Cassidy thought the proposal would protect the county from future development such as the solar farm in Panoche Valley, she said.

“This sounds – and I never thought I would say this – like a good idea,” she said. “If you don’t want to do it, you don’t have to. ”

At the last of six scoping meetings, the federal agency’s Chief of Refuge Planning Mark Pelz introduced the project – and some details – before taking comments from the public.

Pelz made it clear that the proposal is based off maps created by the California Rangeland Conservation Coalition, which includes 100 agricultural organizations and environmental interest groups, but not all groups have agreed to the project.

“This is a Fish and Wildlife proposal – we developed it,” Pelz said. “There are diverse members in the coalition and a lot of members haven’t had a chance to decide whether or not to support it. We are just starting the process.”

The presentation did not include details on what the easement proposal would look like and what types of restrictions it could have.

“That is what this is for,” he said. “We are still trying to figure that out. We are asking you for your input.”

However, Pelz explained that the agreements between the federal government and the landowners would be permanent and could change only if both parties agreed. The government would not have the ability to change the agreement without the landowners’ permission.

“Basically, both parties have to agree to it,” he said. “The owner controls access and maintains all rights not specifically prohibited by the easement.”

As currently planned, a member of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service will check on the property to see if it’s properly maintained, but they won’t be intrusive, Pelz said.

“The easement language specifies when and how we will monitor,” he said. “All we’re interested in is the terms of the easement. So let’s say it’s development – we just want to make sure you’re not developing and putting a Starbucks on it.”

And easements can be negotiated, he said.

“There is a lot of flexibility,” Pelz said.

Three other members of the agency, two of which answered and responded to questions, joined Pelz. When comments were made from the public, ideas were written on four boards around the room.

A majority of attendees, though, spoke out against the proposal, questioning the need and the involvement of the federal government.

Some who spoke out worried that if people disagreed with the project, the government would pursue eminent domain on the area to circumvent the easement plan.

Others, including county Supervisor Jerry Muenzer, wanted to know why the funding for the Land and Water Conservation Fund – which comes from oil rig royalties – couldn’t be pushed into the Williamson Act, a state conservation agreement that is slowly ending because of a lack of state funding.

Pelz explained the funding couldn’t be funneled to other projects because of constitutional reasons.

“With the Land and Water Conservation Fund the way that it is written now, there is no way to use that,” Pelz said. “It’s called Land and Water Conservation Act and there is no way to use that. It’s a great idea. The Williamson Act has been a great success and I think it is a model for the rest of the country.”

Others questioned if the easement would bring tax breaks, if the easement agreements would be public records and how each property would be appraised.

There would be no tax breaks, but property values would decrease, Fish and Wildlife representative Shawn Milar said.

Milar said the public could view and compare easement agreements because they would be public records. Also, a third-party appraiser would determine the value of the property and how much the government would pay the landowner.

“The Fish and Wildlife does not do the appraising,” he said.

But overall, Pelz wanted the landowners to know that the proposal wouldn’t hinder their right to make money, he said.

“Our position is, we want the landowner to be able to make a living on the property because we feel the wildlife value that is provided to us by the land staying in ranching is the best use,” he said. “And we don’t want to get down into the weeds by telling you how many cattle you can have on your land.”