This week I compare CalPERS pension benefits to other public retirement programs using average or median data as reported by the various agencies. If your personal pension does not measure up it’s because individual pensions are variable based on many formula factors.

I used recent data as a measure of where the system is today rather than historically. While more than 9,000 annual CalPERS pensions exceed $100,000, that’s only 2 percent of all retirees. However, the number is growing. Fully 1,533 new retirees received pensions of $100,000 per year or more in FY 2009-2010. CalPERS has recently focused on whether some of the highest pensions in the system are justified since the Bell, Calif., scandal.

Reminder, Social Security was not designed to be a worker’s only source of retirement income, but part of a comprehensive retirement program. At the local county and city level, only the San Benito County Miscellaneous Employees participated in a coordinated CalPERS/Social Security retirement system. County public safety, Hollister miscellaneous employees, and Hollister public safety employees do not participate in the Social Security system. For the county miscellaneous employees, both employers and employees pay the regular Social Security taxes.

The ultimate result of a coordinated Social Security retirement also depends on previous or subsequent employment. Those in a coordinated system receive approximately 5 percent less in CalPERS retirement payments until they are eligible for Social Security – at which time they get a blended retirement, which typically adds $1,000 a month to the CalPERS payment.

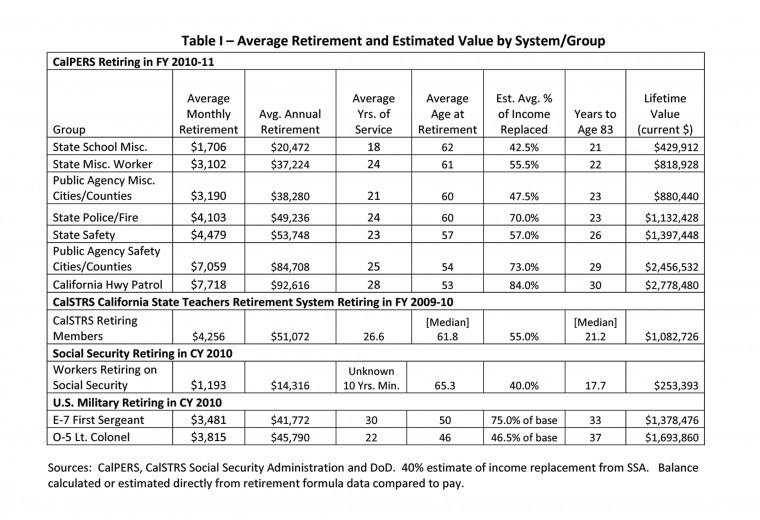

Overall, CalPERS members retiring in FY 2010-11 averaged $3,065 per month, or $36,780 per year, in retirement pay. They had an average of 20 years service, and averaged 60 years of age at retirement. However, the averages tell only part of the story because there were large disparities between groups of retirees. See Table I provided – Average Retirement and Estimated Value by System/Group – for data and comparisons.

It’s possible that, over time, inflation will eat into the purchasing power of a defined benefit. This is addressed by a cost-of-living adjustment, or COLA. According to CalPERS: “most State retirees, and all school retirees, have their COLA limited to a maximum of 2 percent (compounded) annually. Public agencies can contract for 2, 3, 4, or 5 percent cost-of-living adjustments.” The definition of the COLA base year index and complex calculations are beyond the scope of these columns – just know it’s there.

Just in case COLA cannot keep up, certain long-term CalPERS employees have another benefit called the purchasing power protection allowance, or PPPA. The PPPA is a supplementary “cost-of-living” benefit paid when the retiree’s benefits fall below 75 percent of their original purchasing power; it is paid in addition to COLA. It is designed to restore purchasing power to at least 75 percent of the original retirement benefit. Though there is no set timeframe for PPPA, members do not usually receive this adjustment until 25 or more years into retirement.

The other foreseeable threat to a defined benefit plan is the death of the recipient. CalPERS allows employers to offer a range of modest and generally low-cost Survivor Continuance and Survivor Benefit options depending on several factors such as whether the employees are on Social Security. Example, the City of Hollister, a non-Social Security employer offers the 1959 Survivor Benefit Program at Level 4 that provides $950 a month to one survivor, $1,900 for two survivors and $2,280 for three or more survivors as a city-paid benefit.

The best measure is the cost of the CalPERS pension system to the local taxpayers and that’s the subject for next week.

Marty Richman is a Hollister resident. His column appears Tuesdays.