The abandoned mercury-mining town of New Idria goes on the

market for $7 million

The infamous New Idria mercury mine and its rusting ghost town,

once home to 600 people before the 20th Century, is up for sale:

just $7 million

– orange creek and all.

The abandoned mercury-mining town of New Idria goes on the market for $7 million

The infamous New Idria mercury mine and its rusting ghost town, once home to 600 people before the 20th Century, is up for sale: just $7 million – orange creek and all.

New Idria, which sits at the foot of San Benito Mountain in remote south San Benito County, was the world’s second largest producer of mercury during its heyday. The mine opened in 1856 and finally closed more than a century later in 1971 after the health risks of mercury became more known.

The mine’s legacy is a creek that flows downstream that is bright fluorescent orange during the dry season. During the wet season it flows east to the Central Valley, hooking up with other waterways that eventually flow into the Sacramento Delta and the San Francisco Bay.

The 868-acre property is listed on the Multiple Listing Service for real estate – as well as the San Francisco-based Craigslist.org, a site for classified ads.

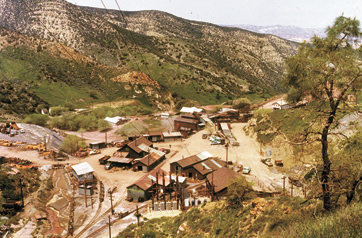

“It consists of more than a dozen vintage fixer upper/ knocker downer buildings, and a large smelter/mill at one end of town,” the ad states. “The San Carlos Creek passes through the middle of the property.”

What the ad doesn’t mention is that New Idria is the source point for one of the state’s most egregious cases of what’s called acid mine drainage. In New Idria’s case, that drainage includes chemicals and heavy metals such as selenium, nickel, boron, manganese and alum.

The most hazardous element, however, coursing through the pumpkin-colored San Carlos is methylmercury, the most lethal and organic form of mercury. It is colorless, odorless, and bioaccumulates in animal, aquatic and human tissue, according to scientists who have studied the watershed for a quarter of a century.

The real-estate broker handling the selling of the property is Carol Ann Wegenast of ASAP Real Estate in Redwood City. Wegenast visited the property in June and wrote the description on Craigslist.

When asked if she had noticed the water was orange, Wegenast said, “I noticed it was colored but I didn’t know what it was from. Some people have said that’s from iron, but when I try to get information from (government) agencies on it, I can’t find out a thing.”

The orange color, actually, comes from iron sulfide accumulated in runoff from the mountainous tailing piles of cooked cinnabar ore between which the creek travels. as well as the nearly 80 miles of tunnels buried within the mountain that was mined for more than a century.

The town itself is equipped with untainted water coming from a reservoir a few miles above the town. The pipeline leads to spigots in town, but the water is not shared with neighbors downstream.

The history of the New Idria Mercury Mine is a tumultuous one involving swindlers and transactions that went sour dating back to the late 1800s.

The current owner is Sylvester Herring of San Jose, who for years since his ownership in the late 1980s operated a drug rehabilitation center at the site, called Futures Foundation. Many of the residents were state-ordered drug offenders swapping jail time for work and residence at the sprawling compound.

They lived in the dilapidated outbuildings leftover from the mining days, including a defunct post office, a mine rescue station, small cabins and miners’ dormitories.

During the time when it was a drug rehab, New Idria also became an illegal garbage dump. For 15 years Herring operated a building deconstruction business in San Jose, and had his “family members” – the drug residents of New Idria – haul truckloads of landfill material to New Idria and dump it off the highest tailing pile on the side of a mountain, according to court documents. For years, skeletons of dead cars, batteries, scrap metal, PCBs, sheetrock and drums of mystery substances littered the town. Later, the state Department of Toxic Substances charged Herring, made him pay for most of the cleanup and pay a hefty fine for the act. Herring recently got off probation for the offense.

Agent Ed Doty of the state EPA’s Toxic Substances Criminal Division, who led the effort for the garbage cleanup in New Idria, was surprised when told the property was selling for $7 million.

“Wow, that’s funny,” Doty said.

Looming above the town is the mountain that drains “Portal 10.” A ribbon of orange water exudes from this portal and runs through the decaying town, becoming what is known as the San Carlos Creek.

The hazardous water content in the San Carlos watershed has been documented in reports by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (1997), the Central Valley Regional Water Quality Control Board in 2003, and in a report completed by earth and marine scientist Dr. Khalil Abu-Saba of Santa Cruz. Abu-Saba was hired by the county in 2002 to elicit help from outside state and government agencies to start a cleanup effort on the site.

Lonnie Wass, spokesman for the Central Valley water board, said there have been starts and stops in addressing the acid mine drainage at New Idria for decades. He says the cleanup effort is not yet dead, and currently his agency is trying to arrange another meeting with the federal EPA on the issue.

“There’s still a lot up in the air with New Idria, but there’s still money available for this,” Wass said.

Abu-Saba and Mandy Rose, the director of San Benito County’s Integrated Waste Management agency, obtained a $200,000 federal EPA Brownsfield grant in 2004 to conduct a responsible party search and assessment of the pollution.

Last year, one of what could be a long list of responsible parties has come forward, called Buckhorn, a subsidiary of Akron, Ohio-based Meyers Corp., which owned the mine at one point for a period of only five years. Hence, the company is only willing to contribute to five years worth of cleanup in what is a 120-year environmental disaster. Meyers Corp. also once owned the larger but now remediated Almaden Mine in San Jose, and was made to pay millions for its cleanup in the 1980s.

Rose says it is nearly unheard of for a responsible party to raise their hand in such cases.

“It’s very incredibly positive that a responsible party came forward,” she said. “It will start the process. Something’s going to happen – maybe this year, maybe next year, but something will happen.”

There is still $150,000 left from the Brownsfield grant, but time is running out. According to EPA rules, the county has only a few more months to spend it, but Rose is still waiting to hear from the agency for permission to do so. The money could possibly go for work by a research group from Stanford University, which has studied the New Idria site for 35 years. The group, hopefully, will be able to put together an assessment and engineering cleanup plan for the mine.

Having learned of the pollution emanating from New Idria, Wegenast is undeterred in her efforts to sell it.

“For someone who has deep pockets, $7 million isn’t a lot of money,” Wegenast said. “There are a lot of interesting buildings up there that could be restored to preserve history.”

But to sweeten the pot, Wegenast is offering a $50,000 commission to any buyer’s agent.

“It’s 868 acres,” added Wegenast. “If 68 acres are polluted, doesn’t that mean 800 are good?”

For those interested in buying a mining ghost town with a scenic orange creek flowing from it, call Carol Ann Wegenast at 650-766-0499 or email her at ca*********@*******al.net.