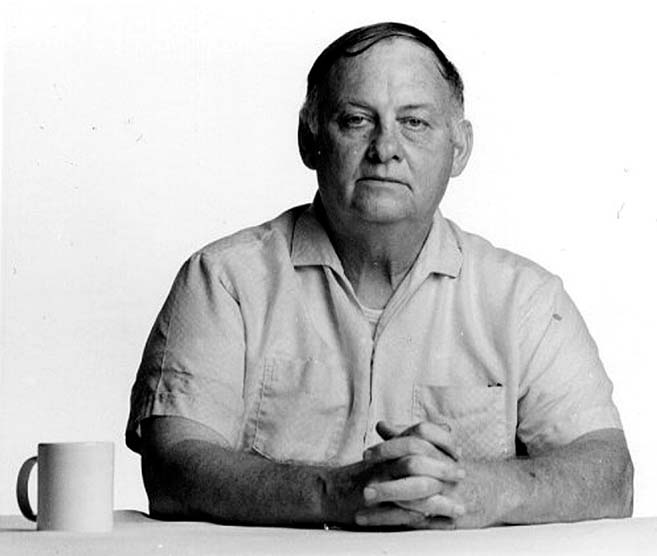

To peers, he was dry in wit, kind, generous, at times stubborn,

always a gentleman and forever open for conversation. As a writer,

he was a newsman by trade, a poet at heart and a grammarian before

anything.

Herman Wrede told stories.

An English purist, a career journalist, an admirer of good literature and to many, a dear friend, the 74-year-old Wrede died at his Hollister home last week.

To peers, he was dry in wit, kind, generous, at times stubborn, always a gentleman and forever open for conversation. As a writer, he was a newsman by trade, a poet at heart and a grammarian before anything.

He moved to Hollister in 1968 with his family to become editor of the Hollister Free Lance, a post he held for nine years. He later became the first editor of The Pinnacle and, in his later years, wrote columns for both local newspapers.

He wrote two books titled “Day by Day” – one in 1995, a second 10 years later – in which he chronicled something about each day in San Benito County throughout a year. He also contributed a column called “On the Line” for a local Web site. And at death, he had been working on a book about his favorite writer, William Shakespeare.

Wrede passed away at some point between last Wednesday and Sunday. Acquaintances hadn’t seen him in a few days, and his landlord found him Sunday at his Hollister home.

He’s survived by his spouse, Sigrid, of Costa Mesa, along with two sons and a daughter.

Born in Toledo, Ohio, Wrede had a blue-collar upbringing. He was a laborer and a soldier in the U.S. Army before entering journalism out of college.

Though not a native to San Benito County, he adored his adopted home. He rarely missed a big event downtown or a monthly chamber of commerce mixer. He knew the local history as well as anyone, if not better. He had an extraordinary memory, never forgot a birthday if he heard it, likely asked it, once.

He was trusted by friends and earned enough respect among some of the more influential residents in these parts to gain entry into the “Jolly Boys Club” – a little known yet prestigious monthly gathering, usually over breakfast, among the likes of Wrede, Marshal Robbie Scattini, the late George Kincade, former Judge Tom Breen and Hollister True Value owner Fernando Gonzalez. New members, allowed only with someone’s death, require anonymous approval.

They merely eat, and bond.

To this day, they’re brutally honest with one another.

Scattini, one of Wrede’s closest companions, described his serious but jestful lack of patience for Wrede’s almost constantly dry tone, a layered humor requiring patience, close attention.

Wrede, his remaining hair swiped over the forehead, with a half-cocked almost self-deprecating smile, never stopped trying.

“He had so many of them,” Scattini said. “I can’t even remember. His jokes used to be so dry, I didn’t even pay attention. I used to tell him, ‘I don’t want to hear anymore of your damn jokes.'”

Scattini remained close with Wrede until his death, had planned to drive him to Wednesday’s chamber mixer at Rancho Quien Sabe, picked him up from the airport a couple of months ago when he returned from his last trip to Ohio, a flight he took on a whim when a friend back in the Midwest, who had a stockpile of air miles, made the generous offer.

Almost every facet of Wrede’s personal style, especially his humor, was defined by an element of surprise. Even his charity.

Another of Wrede’s friends, Gene O’Neill, recalled how many years ago he and Herman had been at Johnny’s Barber Shop, where Herman was a regular. Wrede had his haircut first, and when O’Neill went to pay his bill, the barber told him Wrede had picked up his tab as well.

“He said Herman paid my bill. He paid what I always got charged. I asked ‘Why?'”

To which the barber responded, “I guess he likes you.”

“It was great in a way,” O’Neill said. “In a way, it was kind of funny.”

Wrede usually acted charitably behind the scenes. He made a habit each Christmas in recent years of commissioning Irene Agredano, his landlord, to deliver anonymous cash gifts to friends or organizations, sometimes $50, sometimes $100. Despite lacking in wealth, he gave what he could.

He loved his friends, he loved literature and he loved food. Wrede often raved about the old Little Sunshine Cafe at Hazel Hawkins Memorial Hospital, mostly because it served his favorite bowl of clam chowder. He’d prefer a Johnny’s Bar and Grill burger over just about anything. He wasn’t a fancy guy by any means. He was just fine being equal.

When finished volunteering on Thanksgiving and Christmas for the Marley Holte dinners, he always sat with the very people he had just served and enjoyed his own holiday meals. He often raved about the food, looked forward to the camaraderie, and felt as comfortable talking to a poverty-stricken stranger at the Thanksgiving dinner table as he was a highly influential politician on the street, or an old friend.

Most of all, when he could, he gravitated toward people. As an old newsman like Wrede understood, and it showed in every bit of his writing, he needed them. They were, in the end, his life’s work.