Where have the workers gone? One of the biggest problems lurking

in the nation’s economic future may be the sudden lack of growth in

the civilian labor force. That’s the number of people employed plus

those actively seeking employment.

Where have the workers gone? One of the biggest problems lurking in the nation’s economic future may be the sudden lack of growth in the civilian labor force. That’s the number of people employed plus those actively seeking employment.

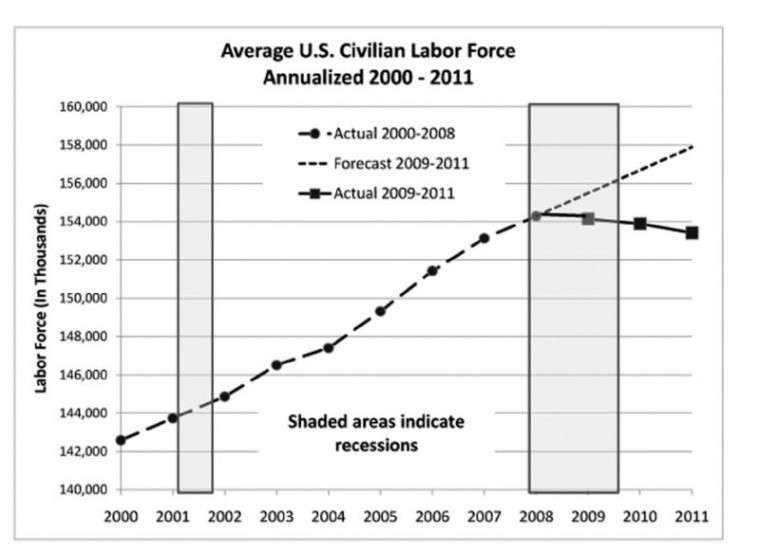

In both 2009 and 2010, the annual growth rate of the civilian labor force contracted – it fell below zero. An annual contraction had happened only once in the previous 60 years, 1951. Now it has happened two years in a row. This year’s data through July has produced similar results. Things might change, but two full years and seven months proves the drop was not merely a fluke.

The impact has been that 874,000 individuals dropped out of the labor force since 2008 and more than 3.1 million new members, forecasted from population growth and legal immigration, never appeared. Added together, about 4 million potential workers either left or never entered the labor force over the last two-and-a-half years.

The civilian labor force normally grows as the population increases. Based on that increase and participation rate – the percent that are working or looking for a job – the labor force should have grown a minimum of 1.2 million a year, but it contracted instead. The size of the labor force depends on those two factors, the population growth of non-institutionalized civilians 16 years of age and older and the participation rate.

From 1980 to 1999, the average growth of the labor force was 1.7 million a year. The lowest year was 1991 when the labor force grew by 506,000. The average annual growth from 2000 through 2008 was 1.65 million a year. The lowest year was 2004 when the labor force grew by 891,000.

With a growth rate below zero the obvious questions are, will those 4 million people reenter the labor force and, if so, when? If not, how will the reduced working population support them?

People out of the labor force can represent economic potential, especially those who are continuing their education or training instead of seeking employment due to poor economic conditions. However, that potential does not last forever especially for older workers. The longer they are out of the labor force the more difficult it will be to come back.

The 18-month recession officially ended more than two years ago in June 2009; yet the flattening of the labor force’s growth continues and that influences the unemployment rate. As long as people keep dropping out of the labor force, the rate will be artificially lowered; those not in the labor force are not counted as unemployed. On the other hand, improving employment prospects have the potential to draw the ‘dropouts’ back into the labor force keeping the unemployment rate high even as jobs are added. We are in uncharted waters; one must be very careful when evaluating the headline unemployment numbers.

Several recent articles have dealt with the falling participation rate. With 240 million qualified members of the population, a one percent drop in the participation rate means a 2.4 million drop the civilian labor force. From 2000 to 2004 the participation rate fell from 67 percent to 66 percent and then it held steady for four years. From 2009 to July 2011, the participation rate fell another 1.9 percent to 64.1 percent. The drops since 2000 equate to a labor force reduction in of 9.4 million people.

It appears that more people are dropping out of the labor force during difficult economic times and they are not coming back – even when things get better.

Marty Richman is a Hollister resident.