Over the years, County Supervisor Jerry Muenzer’s Tres Pinos property has drawn intermittent interest from people in the oil industry. From time to time, he’s been paid for the right to survey his land in search of deposits.

Usually, they would agree on an annual contract that might last two or three years. And while the oil men have come and gone, such surveying never amounted to anyone striking it rich, or really striking anything of value for that matter.

“They would go away,” Muenzer said, “and somebody else would come along.”

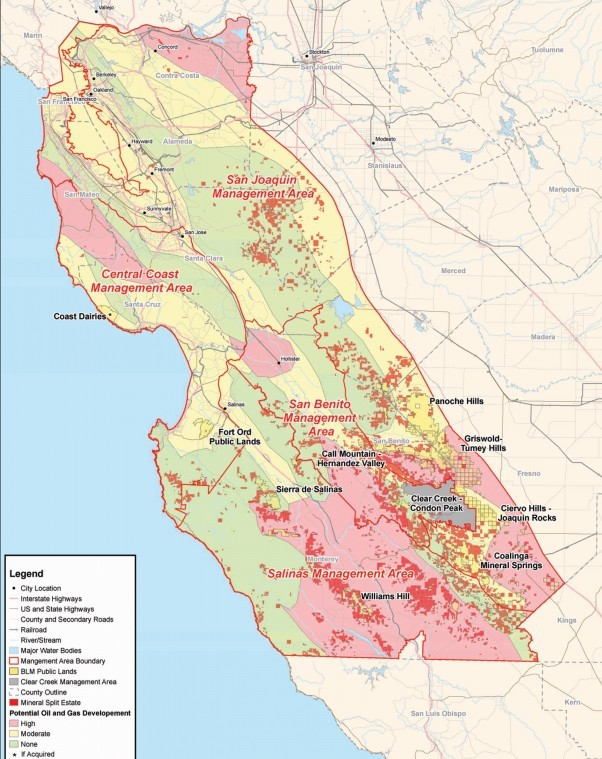

Muenzer’s case involves just one property’s experience but reflects a cyclical, yet historically spotty pursuit of oil in San Benito County and the entire Monterey Shale – 1,752 square miles stocked with what amounts to the largest “play” in the lower 48 states with nearly two-thirds of the known shale resources.

Exploration here has been cyclical through the decades, starting in the late 19th century, but with ever-increasing oil prices at about $90 a barrel this week and emergence of advancing technologies allowing access to previously unrecoverable reserves, the energy industry is once again taking notice of the region’s prospects, said Jeff Vaughn, owner of Bakersfield-based Vaughn Exploration, Inc.

“California is an amazingly rich state for oil and gas, and it’s all up and down the state,” Vaughn said.

Forget about the Gold Rush. This region and state might need to brace for the highest-viscosity wave to ever hit the shores of California – home to the Monterey Shale and its estimated 15.4 billion barrels of recoverable oil, and a state almost certain to experience a growing debate over environmental impacts of new extraction methods, broader economic potential and whether it is even financially or technically feasible for investors to extract at a fast enough production rate for exploration to pencil out.

The No-Frack Pack

A growing number of Aromas residents also have taken notice – but from a negative light, anxious with uncertainty over their hometown of about 3,000 people where a company recently conducted visible, nerve-rattling seismic testing with a primary goal of finding oil or gas.

That company, Freedom Resources, spent several weeks in June and July surveying the geology within and near the Wilson Quarry – with much of the land at stake owned by Graniterock, which OK’d the work – using newly available imaging technology. Freedom Resources’ intention was finding oil or gas, but Graniterock’s spokesman underscored the company’s interest was rooted in learning more about the quarry’s makeup and possibly supplanting archaic, expensive methods to survey its deposits.

Area opponents aren’t necessarily buying the local company’s public reasoning, though, as a group called “Aromas Cares about our Environment” sprouted on the heels of the survey work and has rapidly expanded its membership. Driven by a Facebook page eclipsing 175 “friends” as of this week, the opposition plans to hold its latest organized forum next Wednesday at the Aromas Grange Hall.

They have the same concerns as other fracking opponents throughout the nation, particularly areas where the practice was determined to cause contamination in drinking water sources – as it involves use of water and chemicals to fracture rock deep beneath the earth and release petroleum, often higher yields than otherwise attainable.

Graniterock spokesman Keith Severson acknowledged the business failed to get out fast enough in communicating with the public over the Freedom Resources work. Before Graniterock had a chance to address the community – which it did at a July forum and in an “open letter” from the CEO – locals’ speculation about all the trucks and surveying equipment spurred incensed talk from the opposition over the prospect that Graniterock may use the information to drill for oil, or possibly employ or allow the highly controversial method of hydraulic fracturing, called “fracking,” to acquire natural gas.

Severson pointed out there has been oil exploration in that area for more than 100 years and said “oil and rock don’t mix well,” alluding to the quarry and 112-year-old granite harvesting business.

“You can suppose there’s oil out there somewhere,” he said. “It would not be in our best interest to find oil. Natural gas hasn’t even been discussed. Fracking, a very kind of desperate attempt at getting natural gas, is even further removed.

“Nobody at Graniterock has ever uttered the word ‘natural gas’ or ‘fracking.’”

The company spokesman, though, would not rule out possible oil or gas extraction on the site at some point.

“I can’t comment, other than what the letter says,” Severson said.

Reports resulting from the Freedom Resources study are due back to Graniterock in a couple of months, he said.

“We all understand the concerns,” he said. “We understand that fracking is a concern for people all across the country and everywhere. We totally understand that. We also understand, even oil exploration is a concern. Harvesting rock is a concern.

“But as I have said, and as we sort of intimate in the letter, in this country, in this state, particularly in these three counties (in which Aromas is situated), if somebody’s going to do something, there are tons and tons of regulations.”

Without a solidified assurance, however, skepticism will likely hang over Aromas and its environmentally conscious-leaning populace.

Aromas resident Maureen Cain helped to start the Aromas Cares group and said suspicions flared after the surveying company had stopped at the water district office, where she works, and asked locations for pipes because they were going to be shaking the ground. From there, locals started questioning the unusual presence from the outside firm and soon realized it had done oil exploration work elsewhere.

“The conversation just started,” Cain said. “It became a big ball rolling down the hill so fast.”

Pushing that ball are perceived environmental risks involved with fracking. Cain is worried about chemicals filtering into the groundwater system and drinking supply, but also the fact that Aromas already has a scarcity of water. Advocates of fracking, particularly the natural gas industry, have contended it’s been safe for decades and is getting even safer. Still, California is among a vast majority of states without environmental regulations specific to fracking. At the local level, the county issues permits for road-related work and extraction from wells, but does not address hydraulic fracturing to this point.

“The problem is, of course, the high water use,” she said, “which in our area, we don’t have a lot of water anyway. Using water to do this is not a great idea. Then there’s the chemical. Then wastewater comes out of it that is very toxic, apparently. Those are all issues.”

Exploration is nothing new

While the use of fracking has more recently expanded – the practice actually goes back to the 1940s but became commercially viable in the late 1990s – oil exploration is nothing new to San Benito County.

There was some of it at the turn of the 20th century in the Bitterwater area of south county, said Roy Lewis, a semi-retired appraiser working in the tax assessor’s office the past 49 years. The “Vallecitos Field” about halfway between Panoche and New Idria was a hot spot in the 1950s and largely involved the Shell and Mobil oil companies. But production there dwindled and the two companies were both gone around 35 years ago, Lewis said.

Around four decades ago, a company called Blackhawk Oil drilled two new wells in the Vallecitos Field and had immense success. Three years later, though, it had “dried up to a trickle” and within a couple more years was abandoned. Since then, any activity has been on a smaller scale, irregular in frequency.

One of the relatively larger operators most recently permitted here was a Kansas company called Lario Gas & Oil – approved in 2007 to drill on about 800 acres, two separate properties, in the Flint Hills near Highway 156. Lario was unsuccessful and abandoned the sites in 2011.

“I don’t know what these people were thinking,” said Lewis, whose office gets involved at the “tail end” of the permitting process, when applicants are ready to break ground. “They sure did drill a big hole in the ground in the Flint Hills.”

Interest still appears to be simmering, though, reflected in the work at Graniterock and scattering of oil wells and surveying work under way throughout the county.

There are four general locations where oil drilling is occurring here, Lewis said. In the Vallecitos Field – the only site with more than one operator – there are five wells. Two wells are permitted in Silver Creek, between Vallecitos and New Idria. There are eight wells in Bitterwater, and then two gas wells near Buena Vista Road.

While they are not “pumping like crazy” yet, Lewis acknowledged the market has stirred a revived intrigue from investors.

“If they drill a well a couple miles deep, as has been done several times over the past decades, they usually wind up with nothing,” Lewis said.

He estimated it costs the investors millions of dollars.

“Maybe some day somebody will hit something,” he said. “These guys are like the old gold miners, but they’re playing with big dollars.”

Unlocking the potential

For those investors, some believe, it is just a matter of time when the science will eventually offset natural deterrents. Others are more skeptical.

Despite the Monterey Shale’s immensity on paper, a report from the Wall Street firm AllianceBernstein was released Tuesday called “The Mystery of the Missing Monterey Shale.” That document contends the shale reservoir has not lived up to expectations that it would add 300,000 barrels a day to California oil production – with possible reasons for the formation’s underperformance including its abundance of natural faults, low reservoir pressure and a geological profile somewhat resistant to fracking.

Vaughn, who owns the Bakersfield exploration firm and has worked with Lario Oil & Gas, believes the industry is starting to “unlock the potential” with new technologies. He pointed to fracking and surmised: Whereas traditional drilling might produce a barrel or two a day, hydraulic fracturing might yield a couple hundred barrels.

“It really brought the price of natural gas way down,” he said of fracking. “It’s a great thing for the consumer and the U.S., that we’ve got so much of this resource.”

Along with advancing technology, investors have been motivated by the oil market with a price remaining “very good for the past couple years,” said Vaughn, who expects continued exploration here in the coming years.

“Oil fields never seem to die,” he said. “As technology grows, you go back – somebody may have even completely abandoned a field. It’s a story that keeps repeating itself over and over and over again.”

The Bakersfield Californian, part of the MCT wire service, contributed to this report in the paragraph noting the AllianceBernstein report released this week.