Despite recent outbreaks, death from E. coli rare

Despite recent outbreaks, death from E. coli rare

Stomach cramps. Fever. Vomiting. Diarrhea.

Those are the most common symptoms of food-borne illnesses.

Nearly a quarter of Americans suffer them year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. But rarely is the disease fatal except in the very old, very young or those with other illnesses that compromise the immune system.

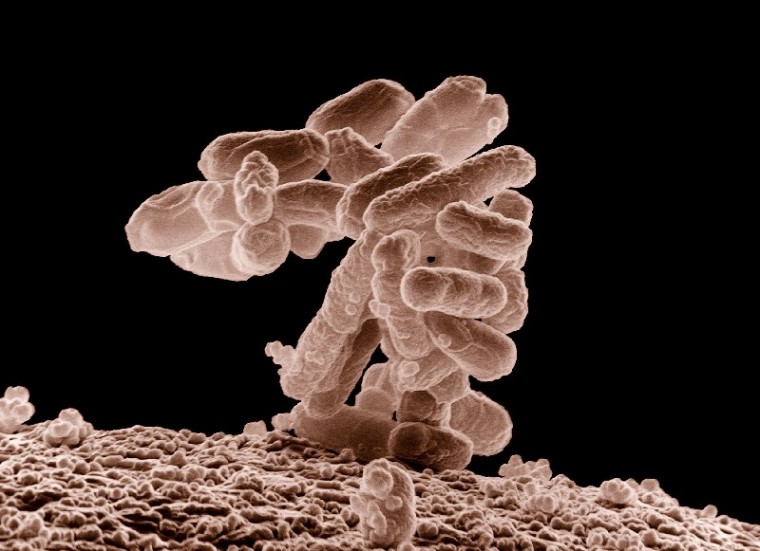

The most common causes of food-borne illnesses include E. coli, which was the culprit in a recent spat of upset stomachs on the East Coast and contaminated spinach earlier this year; campylobacter which is passed along from undercooked poultry; and salmonella which can be passed from birds, reptiles and mammals. Shigella is another common bacteria that is spread from person to person and can contaminate food prepared by someone with the bug.

“For people who are relatively healthy, it’s miserable but they will get over it,” said Kathleen Boulware, a public health nurse for San Benito County. “Most people don’t ever get diagnosed. They have vomiting and diarrhea. They just picked something up that lasts a day or two or three.”

Less than .1 percent of the U. S. population is hospitalized each year with food-borne illnesses and only 1 percent of those hospitalized die from the illnesses.

Though it is often a case of being uncomfortable, Boulware said, some people do develop more severe symptoms.

A common complication from E. coli poisoning is hemolytic uremic syndrome. When people develop HUS, their body destroys red blood cells and their kidneys fail. With intensive treatment less than 3 to 5 percent of people with HUS will die, though some have mild abnormalities in their kidney function later in life and other complications such as blindness or paralysis.

Most people do not seek treatment for food-borne illnesses.

“Once you get it, there isn’t a lot of treatment for it,” Boulware said. “You don’t want to stop the diarrhea because that is the body getting rid of the bacteria.”

Most health officials do not recommend anti-diarrheal drugs or antibiotics. Most food-borne illnesses run their course in five to 10 days without medical intervention.

“It is one of those things were prevention is more the way to go,” Boulware said. “The organisms are easily killed by heat. It’s raw food you have to take other precautions with.”

Researchers first recognized the strain O 157:H7 when it caused a severe outbreak in 1982 linked to contaminated hamburgers, according to the CDC. Since then undercooked ground beef has remained the cause of more infections than any other food.

There’s been a clear decline in E. coli outbreaks involving ground beef, thanks to changes in the beef industry, said Dr. Christopher Braden, a U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention epidemiologist leading the investigation of the recent Taco Bell illnesses. The rate of E. coli sicknesses has dropped 29 percent since the mid 1990s.

But E. coli illnesses involving leafy green vegetables have continued, at a rate of one to five outbreaks a year, he said.

E. coli is found in cattle manure, which is often used in the course of growing produce. Leafy greens such as spinach and lettuce need to be washed thoroughly before eating if they are not cooked. Even that is not a guarantee that all the bacteria will be scrubbed away, according to the CDC.

Tracking the illnesses can prove tricky and the CDC still has not issued an official cause of the Taco Bell outbreaks. By the time victims got sick, went to the doctor and had tests done to diagnose the cause, the contaminated food was probably gone, noted Jean Halloran, a food policy expert with Consumers Union.

Sometimes, health investigators get a break. In the recent investigation into tainted spinach, sick people still had bags of the bacteria-tainted greens sitting in their refrigerators.

Those bags of spinach were “the smoking gun” that helped the U.S. Food and Drug Administration trace the outbreak all the way back to the California fields that grew the infected produce, said Michael Doyle, director of the University of Georgia’s Center for Food Safety who was hired by Taco Bell to help it test its food.

“The spinach outbreak was an unusual circumstance. Everything kind of fell into place,” Doyle said.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.

Melissa Flores can be reached at mf*****@**********ws.com.