For Dan Straus, the Lick Fire was a lesson in loss. During the

fire’s week-long rage in 2007, he lost two cabins, his shed, and a

prized possession passed down from his late father

– 42 leaves of meticulous calculations written by his father’s

colleague, Albert Einstein.

For Dan Straus, the Lick Fire was a lesson in loss. During the fire’s week-long rage in 2007, he lost two cabins, his shed, and a prized possession passed down from his late father – 42 leaves of meticulous calculations written by his father’s colleague, Albert Einstein.

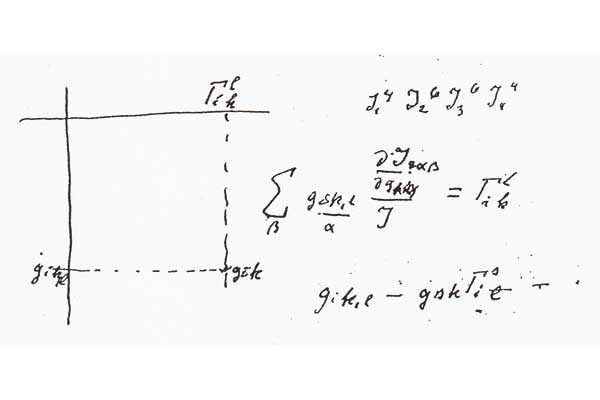

The wildfire that gobbled up almost 50,000 acres – roughly half – of Henry W. Coe State Park, the largest state park in northern California, also consumed a stack of pages lined with the Nobel Prize winner’s painstaking computations interspersed with delicately scripted notes and the occasional diagram. Margaret Pavese, the San Juan Bautista schoolteacher responsible for setting the blaze, settled a criminal suit against her that yielded a $200,000 restitution to the families whose cabins burned, three years of court probation and 250 hours of community service – which she has already completed, Deputy District Attorney Cindy Hendrickson said. However, Pavese and her husband still face two civil lawsuits – one brought on by CalFire seeking $16 million as reimbursement for fighting the fire, and another filed by Straus – a San Jose State University chemistry professor whose father worked alongside the man many referred to as the Father of Modern Physics.

Straus, 54, never met Einstein but fondly remembers his father’s stories of the famed physicist. Mathematician Ernst Straus died in 1983, but the four years he spent working under Einstein at Princeton University’s Institute for Advanced Studies lived on in the relics he bequeathed to his wife and the stories he shared with his sons. Dan Straus laughed out loud when recalling one of his father’s stories about how Einstein, who “was very fond of toys,” received a toy bird that walked with suction cups attached to its feet. Einstein stuck the trinket to the ceiling until the suction cups failed and it fell one day, after which he followed it around with an upside down umbrella to cushion the blow should the toy fall again. Dan Straus also remembered hearing how Einstein, upon hearing that the Straus family’s cat had kittens, canceled several invitations to instead play with the newborn felines.

Back in September 2007 as he was gearing up for classes, Dan Straus, who owns a home in San Jose and owned two small cabins on 40 acres in Henry Coe, took the papers up to the park to make copies and organize them. He left for a backpacking trip in the Sierras the weekend the Lick Fire started, and returned to find his cabins and the possessions inside – including Einstein’s papers – incinerated.

“Everything but the outhouse,” he said wryly. “It was tragic. I was just sick about the whole thing for a quite a while.”

Dan Straus and Pavese reached a settlement earlier this year in terms of his cabin and the other structures that burned, but his and the Paveses’ attorney are currently debating the value of the papers. The Paveses’ attorney is in trial for the next couple weeks and was not available for comment, according to his office staff, and the Paveses did not return a phone call. Though Dan Straus’ complaint does not quote a specific dollar amount, experts place the value of the Einstein papers anywhere from $250,000 to $450,000.

“Einstein autographs, autographed letters and autographed photographs are not uncommon, and many have been sold at auction in recent years (Einstein signed quite a bit of material for charitable purposes),” wrote Howard Rootenberg, director of a rare book business in southern California, in an unofficial appraisal. “However, leaves of Einstein scientific manuscripts are much more scarce, and over the past five years have only come up for auction on a few occasions.”

For example, two leaves of Einstein’s notes on Unified Field Theory fetched $11,245 in 2005 and one leaf containing a series of mathematical equations auctioned for $14,000 in 2004, according to auction records.

Conducting appraisals on documents authored by Nobel winning scientists – “some of the books that have had the greatest effect on civilization” – including first editions by Newton, Copernicus and Darwin, isn’t new to Rootenberg. Yet, “the Einstein stuff is some of the coolest,” he said. “(Einstein) seemed to write on any and everything. His thought process seemed to be that if something came into his head, he would write it down right away.”

Rootenberg said the documents were “irreplaceable.”

Straus may not be able to replace the one-of-a-kind papers, but in the two years since the fire destroyed his property – situated 6.2 miles from the Paveses’ cabin – he and friends have built a new cabin and he’s working on developing a chemical that will help rejuvenate the burned forest floor.

A couple weekends ago, he took a group of students and volunteers out to the park to distribute a chemical compound found in smoke that they whipped up in the lab at San Jose State, Dan Straus said. If all goes well, the compound will induce germination in seeds.

“There are some plants back that never sprout unless there’s a fire,” said Dan Straus, who is also a park volunteer. “They get a whiff of smoke extract and they start coming up.”

The Lick Fire started about 10:30 a.m. Sept. 3, 2007, when Margaret Pavese left an illegal and poorly maintained burn barrel full of paper plates unattended for about three hours, prosecutors said. The flames spread from the bottom of the burn barrel because grass had grown into it and the fire raged for the next eight days, destroying four cabins and 11 outbuildings.

Pavese initially pleaded not guilty to a charge of failing to exercise reasonable care in the disposal of flammable materials and improper use of an incinerator – a misdemeanor that carries up to six months in prison and $1,000 in fines. The district attorney did not pursue felony or arson charges because the fire was not set intentionally, prosecutors said.

The civil lawsuit brought on by CalFire will go to a case management conference Jan. 26 and Dan Straus’ lawsuit will head to a non-binding arbitration hearing later this year, though a definite date has not been set, said Dean Rossi, Dan Straus’ attorney. At that point, a third-party arbitrator will hear the case and give a non-binding decision. If either of the parties don’t agree, the case will go to trial, Rossi said.

“It’ll be so nice to have this settled,” said Dan Straus, who used to bring his mother up to the cabin before she died in June. The papers were part of her estate. “That was my place to get away from everything.”