By LOUISE CHU

SAN FRANCISCO

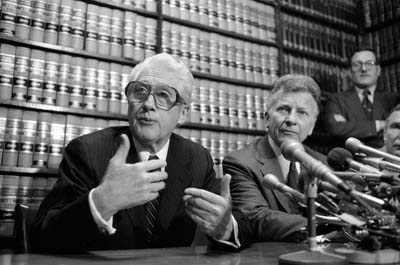

W. Mark Felt, the former FBI second-in-command who revealed himself as “Deep Throat” 30 years after he helped The Washington Post unravel the Watergate scandal, has died. He was 95.

Felt died Thursday at a hospice near his home in Santa Rosa after suffering from congestive heart failure for several months, said family friend John D. O’Connor, who wrote a Vanity Fair article disclosing Felt’s secret in 2005.

The shadowy central figure in one of the most gripping political dramas of the 20th century, Felt insisted his alter ego be kept secret when he leaked damaging information to Post reporter Bob Woodward.

The scandal led to President Richard Nixon’s resignation in 1974, two years after the break-in at the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee in the Watergate office building in Washington.

While some – including Nixon and his aides – speculated that Felt was Deep Throat, he steadfastly denied the accusations until finally coming forward in May 2005.

“I’m the guy they used to call Deep Throat,” Felt told O’Connor for the Vanity Fair article, creating a whirlwind of attention. Weakened by a stroke, he wasn’t doing much talking – he merely waved to the media from the front door of his daughter’s Santa Rosa home.

Critics, including those who went to prison for the Watergate scandal, called him a traitor for betraying the commander in chief. Supporters hailed him as a hero for blowing the whistle on a corrupt administration trying to cover up attempts to sabotage opponents.

In a phone interview Friday, Woodward said despite the criticism and Felt’s own ambivalence, it is clear that Felt should be remembered as a man who did the right thing.

“This is a man who did his duty to the Constitution,” Woodward told The Associated Press.

Just last month, Woodward and onetime partner Carl Bernstein visited Felt in his home. It was the first time Bernstein had met him. Woodward said Felt had flashes of lucidity and still cut the appearance of an FBI agent, sitting straight and stiff and dressed in a red blazer.

Felt had argued with his children over whether to reveal his identity or to take his secret to the grave, O’Connor said. He agonized about what revealing his identity would do to his reputation. Would he be seen as a turncoat or a man of honor?

“People will debate for a long time whether I did the right thing by helping Woodward,” Felt wrote in his 2006 memoir, “A G-Man’s Life: The FBI, ‘Deep Throat’ and the Struggle for Honor in Washington.” ”The bottom line is that we did get the whole truth out, and isn’t that what the FBI is supposed to do?”

Ultimately, his daughter, Joan, persuaded him to go public; after all, Woodward was sure to profit by revealing the secret after Felt died. “We could make at least enough money to pay some bills, like the debt I’ve run up for the kids’ education,” she told her father, according to the Vanity Fair article. “Let’s do it for the family.”

The revelation capped a Washington whodunit that spanned more than three decades and seven presidents. It was the biggest mystery of Watergate, the subject of the best-selling book and hit movie “All the President’s Men,” which inspired a generation of college students to pursue journalism.

In the movie, the enduring image of Deep Throat is of a testy, chain-smoking Hal Holbrook telling Woodward, played by Robert Redford, to “follow the money.”

It was by chance that Felt came to play a pivotal role in the drama.

Back in 1970, Woodward struck up a conversation with Felt while both were waiting in a White House hallway. Felt apparently took a liking to the young Woodward, then a Navy courier, and Woodward kept the relationship going, treating Felt as a mentor as he tried to figure out the ways of Washington.

Later, while Woodward and Bernstein relied on various sources in reporting on Watergate, the man their editor dubbed “Deep Throat” helped to keep them on track and confirm vital information. The Post won a Pulitzer Prize for its Watergate coverage.

The nickname “Deep Throat” was a double entendre: Felt was providing information on the condition of complete anonymity, known as “deep background,” and his actions coincided with a popular 1972 porn movie.

Woodward had phoned Felt within days of the June 1972 burglary at the Watergate.

“He reminded me how he disliked phone calls at the office but said that the Watergate burglary case was going to ‘heat up’ for reasons he could not explain,” Woodward wrote after Felt was named. “He then hung up abruptly.”

Felt helped Woodward link former CIA man Howard Hunt to the break-in. He said the reporter could accurately write that Hunt, whose name was found in the address book of one of the burglars, was a suspect. But Felt told him off the record, insisting that their relationship and Felt’s identity remain secret.

Worried that phones were being tapped, Felt arranged clandestine meetings worthy of a spy novel. Woodward would move a flower pot with a red flag on his balcony if he needed to meet Felt. The G-man would scrawl a time to meet on page 20 of Woodward’s copy of The New York Times and they would rendezvous in a suburban Virginia parking garage in the dead of night.

In his memoir published in April 2006, Felt said he saw himself as a “Lone Ranger” who could help derail a White House cover-up.

Felt wrote that he was upset by the slow pace of the FBI investigation into the Watergate break-in and believed the press could pressure the administration to cooperate.

“From the start, it was clear that senior administration officials were up to their necks in this mess, and that they would stop at nothing to sabotage our investigation,” Felt wrote in his memoir.

Some critics said Felt, a J. Edgar Hoover loyalist, was bitter at being passed over when Nixon appointed an FBI outsider and confidante, L. Patrick Gray, to lead the FBI after Hoover’s death. Gray was later implicated in Watergate abuses.

Felt wrote that he wasn’t motivated by anger. “It is true that I would have welcomed an appointment as FBI director when Hoover died. It is not true that I was jealous of Gray,” he wrote.

Felt was born in Twin Falls, Idaho, and worked for an Idaho senator during graduate school. After law school at George Washington University he spent a year at the Federal Trade Commission. Felt joined the FBI in 1942 and worked as a Nazi hunter during World War II.

Ironically, while providing crucial information to the Post, Felt also was assigned to ferret out the newspaper’s source. The investigation never went anywhere, but plenty of people, including those in the White House at the time, guessed that Felt, who was leading the investigation into Watergate, may have been acting as a double agent.

The Watergate tapes captured White House chief of staff H.R. Haldeman telling Nixon that Felt was the source, but they were afraid to stop him.

Nixon asks: “Somebody in the FBI?”

Haldeman: “Yes, sir. Mark Felt … If we move on him, he’ll go out and unload everything. He knows everything that’s to be known in the FBI.”

Felt left the FBI in 1973 for the lecture circuit. Five years later he was indicted on charges of authorizing FBI break-ins at homes associated with suspected bombers from the 1960s radical group the Weather Underground. President Ronald Reagan pardoned Felt in 1981 while the case was on appeal – a move applauded by Nixon.

Woodward and Bernstein said they wouldn’t reveal the source’s identity until he or she died, and finally confirmed Felt’s role only after he came forward.

O’Connor said Thursday his friend appeared to be at peace since the revelation.

“What I saw was a person that went from a divided personality that carried around this heavy secret to a completely integrated and glowing personality over these past few years once he let the secret out,” he said.

Felt is survived by two children, Joan Felt and Mark Felt Jr., and four grandchildren. His wife, Audrey Felt, died in 1984.

O’Connor said the family would hold a private ceremony early next week and a public memorial service in January, after the holidays.

Associated Press writers Matthew Barakat and Brian Melley contributed to this report.