SBHS students listen to moving recollection from storyteller

about World War II

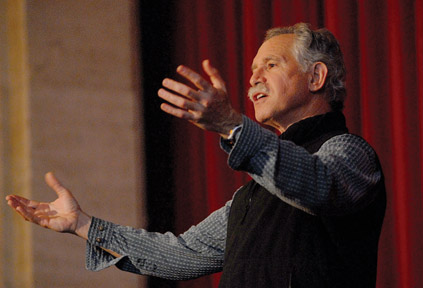

San Benito High School students were prompted to think about

what kind of people they want to be Feb. 23 and 24 when storyteller

Jerry Falek visited campus and talked about his family’s experience

in the Holocaust, including the loss of a dozen relatives.

SBHS students listen to moving recollection from storyteller about World War II

San Benito High School students were prompted to think about what kind of people they want to be Feb. 23 and 24 when storyteller Jerry Falek visited campus and talked about his family’s experience in the Holocaust, including the loss of a dozen relatives.

Falek has been a storyteller for 20 years, and in recent years has incorporated his own personal history into a story about his mother’s choice to immigrate to America during World War II.

“There is one question you have to answer in life,” he said.

Falek talked about how when he was a young man he thought it was a question people answered in their early 20s, after they’d gone to kindergarten up through high school, and hopefully to college.

“But it is something we constantly have to answer,” he said. “What kind of person are you going to be? Are you going to be a person who is loyal to friends or who turns your back on them? Are you going to be an honest person or a dishonest person?”

Before Falek got into his storytelling, he shared with students a bit about genocide, and specifically the Holocaust.

“It was the murder of six million Jews,” he said. “One-third of all the Jews in the world. Imagine if someone killed one-third of the Mexicans or Europeans or Asians.”

He lost 12 people from his own family.

“But there were five million other people who were killed,” he said. “People with strong political views, people with disabilities, gays and lesbians, gypsies and priests. This is my story, but it could just as easily be yours.”

A story for everyone

Tom Rooth, an English teacher at the high school, applied for a grant to fund Falek’s visit. Through support from the Community Foundation and The Baler Foundation, Rooth had Falek lead six sessions of storytelling on campus, followed by a question and answer period with students.

In a letter of intent to the Community Foundation, Rooth wrote: “Our sophomore students begin the spring semester by reading Elie Weisel’s ‘Night,’ a gripping narrative of his experiences surviving Nazi concentration camps as a child, while he lost his entire family.”

He went on to add, “Jerry’s program involves students at the heart level and helps to bring the literature to life.”

Falek told two stories to students in the first Tuesday morning session that kept them engaged and quiet for the first hour of class. The first story was told from the point of view of Falek’s grandfather, his Opa, whom he never met in real life.

When he started talking, he took on a German accent and his gestures changed as he embodied the character on stage. He talked about how his family had long lived in their town in Germany, for 500 years. He owned a shop and played poker with many different men in town, including the mayor. When the mayor told him to get his family out of town because something bad was going to happen, he was stubborn and refused to leave.

“I haven’t done anything wrong,” he said. “I will stand up for myself.”

Nazi soldiers came into town and rounded up 350 Jewish men and put them in jail. The men were released a few weeks later, but it was just the first sign of things to come. He said laws were made that Jews couldn’t go to school and they began to lose their jobs. The family went to a lake they had always visited on vacation, and a sign was posted that said, “No Jews.”

Soon Ruth, Falek’s mother, began approaching her father about leaving the country for America. But he refused to consider it.

“I’m German. You are German,” he said. “I’m not going any place.”

He snapped at his daughter for the only time in his life when she accused him of being scared and frightened. Eventually he relented and helped her get papers in order to go alone to the United States.

Ruth arrived in New York on Feb. 14, 1938 and got a job as a domestic worker for a family. She wrote her family every month and they wrote back. One of the last letters she received from her father said the doors had closed and the family could not get out. In October 1942, Ruth did not receive a letter from her family. Falek said she knew what that meant.

As Falek slipped out of character he said his mom, who died in 2005, started saying something the last 10 years of her life.

“She said, ‘I’ve been lucky all my life. I’ve been lucky all my life except for the Holocaust,'” he said.

“My mother made choices and her father made choices,” he said. “The people around them made choices. Her father chose to be the victim and my mother chose not to.”

But he added that the roles people take on during a tragedy can be complicated, as he segued into his second story about Simon Wiesenthal. Wiesenthal worked to bring Nazi war criminals to justice and founded the Jewish Documentation Center. The Simon Wiesenthal Center, a human rights organization that runs the Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles, is named for him.

A question of forgiveness

Wiesenthal was a college-educated architect when he was taken to a work concentration camp. Falek’s story about him starts when Wiesenthal was 34 years old, in 1942. He was out on an assignment with some other prisoners when they were taken to the town where he had gone to college.

“He would see people he knew and make eye contact and then they would look away,” Falek said. “Most people just looked straight through him, like we do with homeless people today. We make them invisible.”

Soon Wiesenthal realized they were headed to his old university, to the library, which was one of his favorite places. But the building had been transformed into a hospital for wounded Nazi soldiers. The prisoners were made to change bed pans, remove bloody, infected bandages and cart out severed limbs. But a nurse selected Wiesenthal for a special job and took him off to an office that had been the office of his favorite professor in college.

“He closed his eyes and saw the office of a man who had been kind,” Falek said. “He talked with his mentor here, who smoked a pipe of sweet, sweet tobacco.”

But when Wiesenthal opened his eyes, he saw a young Nazi soldier who was dying. The soldier began to tell the story of how he became a Nazi, starting at age 13 when he was just a young boy. Little by little, the commanders pushed the limits of the orders the boys, and eventually men, were willing to take. The man wanted forgiveness for all the things he had done and he wanted that forgiveness from a Jew.

At one moment in the story as Falek related a particular atrocity, the students in the audience fell completely silent with not one student squirming or rustling in their seats.

At the end of the story, Falek asked the audience, “Would you have forgiven him knowing his story and knowing that he was sincere?”

When he finished the story and allowed the students to ask questions, one of the first questions to him was if he would have forgiven the Nazi soldier if he was Wiesenthal.

Repairing the tear in the world

“Forgiveness is a really complicated thing,” Falek said. “The person who is asking for forgiveness has done some soul searching to admit what they did was wrong. They do that alone and they’ve had a lot of time to think about it.”

But Falek said the other part of forgiveness is the person who has been hurt.

“Finding forgiveness is another entire piece,” he said. “If someone has wronged me, I am entitled to say thank you for saying sorry, but these are the ways you hurt me, these are the things you can do to show me you are sorry and make it up to me.”

With that said, Falek said that it is important to take the anger and hatred one might feel and turn it into a positive – what he referred to as “repairing the tear in the world.”

“We need to make sure it doesn’t happen again,” he said.