Local man recalls life as a secret agent

It was 1942 and the outcome of a war that had the world in its

talons was anything but certain.

A young fisherman, newly married, sailed daily out of the harbor

in Monterey, just as his father, an immigrant from the Italian

island of Sicily, did.

Local man recalls life as a secret agent

It was 1942 and the outcome of a war that had the world in its talons was anything but certain.

A young fisherman, newly married, sailed daily out of the harbor in Monterey, just as his father, an immigrant from the Italian island of Sicily, did.

Then the war came knocking, and John Cardinalli was a soldier.

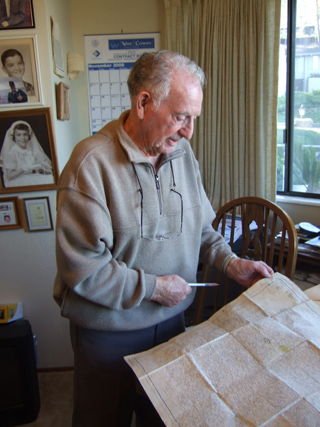

Cardinalli, now 87, agreed last week to talk about his wartime experiences, experiences that the U.S. government asked him to keep to himself for many, many years.

Cardinalli was a spy for the brand-new Office of Strategic Services, the precursor to the Central Intelligence Agency.

“They didn’t call us spies; we were agents,” Cardinalli said as he sat in an office stuffed with wartime memorabilia in his comfortable Ridgemark home.

Cardinalli’s stories sound like the plotline of a novel – make that a shelf full of novels.

Married less than a year to his wife, Josephine, Cardinalli was drafted into the Presidio of Monterey. A battery of aptitude tests revealed that the young man had a hidden talent.

“I excelled in radio – key radio,” Cardinalli said. Communication then was by Morse code, a series of dots and dashes that translated into letters and words. To qualify for service, radio operators had to key four words per minute. Cardinalli ultimately could send more than 20 words per minute.

After bouncing him around the country, the Army landed Cardinalli at Fort Butner in North Carolina. The fort’s most famous alumnus was William J. Donovan, commander of the Fighting 69th in World War I. Ironically, Donovan would be called upon to lead the OSS.

Returning from participating in a referee team for combat maneuvers, Cardinalli happened across a posting at base headquarters.

“There was a big sign there,” Cardinalli recalled. “Wanted: Men for the Office of Strategic Services. Hazardous duty. Second language desired. Radio operators especially needed.”

Fluent in both Italian and English, and with his newfound radio talent, Cardinalli expressed his interest.

“Within a few hours I got a call and was told to report back and get my pack in order. I was told, ‘you’re going to Washington, D.C.'”

Not long after arriving, Cardinalli was told to wait outside a major’s office. Cardinalli, who describes himself as “nosy,” examined the photos on display in the anteroom. He noticed a snuffed out cigarette, and some minor damage to a light fixture. There was a paperclip on the floor.

“He called me in and said, ‘what did you see?'” Cardinalli said. “I described everything, the bent shade, the paperclip, and he said ‘you observe pretty good. Even I didn’t notice the paperclip.'”

Cardinalli was in the OSS. Training involved how to sabotage bridges and rail tracks, hand-to-hand combat and code decryption. They were also taught how to be invisible.

“We were taught how to eat, in a restaurant, say,” Cardinalli said. It’s the details that matter. Cardinalli said one agent was caught behind enemy lines because he used his knife and fork as American children are taught, switching the fork from left to right before taking a bite.

Cardinalli was made an instructor, and posted to the town of Maidenhead, near London.

It was during this time that London and environs were being pounded by Nazi aircraft and unmanned drone airplanes.

“As we were training we used to watch buzzbombs go by. They were pilotless planes. At first they used to run out of fuel and drop straight down. Then they got smart and built them so they glided when the fuel was gone,” Cardinalli said. The silent arrival of a drone was much more effective – and much more terrifying. “We used to run like hell when they came through,” Cardinalli said.

Agents in France would radio to Britain whenever a wave of planes or drones was launched, cueing the Royal Air Force to scramble and meet the planes over the English Channel.

Cardinalli was soon sent into the very heart of the war in Europe. His team received a message that underground resistance forces in the Netherlands needed supplies. The drop was made in one of the country’s signature windmills.

Soon after, Cardinalli accompanied Allied forces advancing into Germany.

The balance of much of the the war in Europe hung at the sole remaining bridge spanning the Rhine, the bridge at Remargen. Before pouring troops and supplies across the narrow span, the Allies needed to gather information about what was waiting for them on the other side.

Cardinalli and another agent, a woman known as “Katja,” were assigned the task. Katja was carefully prepared. Her clothing, right down to her woolen stockings and undergarments, were of German make. She carried German-style bread and sausage, and was careful to take bites out of both so her teeth marks would match. She was given a German-made bicycle, a blanket, a half-full bottle of water and a small portable radio.

Then, on a moonless night, Cardinalli loaded Katja and her things into a small inflatable boat, and launched across the Rhein. The crossing took 45 minutes to an hour.

On the enemy side, Cardinalli the fisherman was careful to drag the boat under cover, then erase the drag marks with a branch.

The two spent a cold night hiding in bushes below a riverside path. Early the next day, cyclists and walkers on their way to work began to appear on the path. Waiting for a gap, Cardinalli ordered Katja to stand at the edge of the path, pretending to tinker with her bike until a large group passed so she could join them and blend in.

Cardinalli remained bivouacked in enemy territory until Katja confirmed that she was settled.

After three nights the signal he was waiting for arrived – “didit, didit” – two double chirps on the radio.

“Radio messages had to be short and sweet,” Cardinalli explained. “Otherwise they’ll pick you up.”

Gestapo agents used radio direction finders to try to zero in on enemy agents. The message Katja sent translates from Morse code into the letters “I, I”

That night, Cardinalli rowed back to Allied territory, to begin the wait for information.

Katja quickly found a place to stay. Her next message broke off in the middle. It was not until much later that the other members of her team learned that she ditched her radio when she thought she was about to be found out.

She began a romantic relationship with a Nazi captain, and the information began to flow.

“She got a lot of good information,” Cardinalli said. Thanks to her, the Allies knew there were tanks and two to three companies of Nazi soldiers waiting for them.

Soon after they poured over the Remargen bridge, the Allied forces met Katja and returned her to her unit.

Soon after, she was killed when her Jeep struck a landmine.

“It was too bad. She was a good agent,” Cardinalli said. “She’d been behind enemy lines a week, maybe longer.”

The wartime memories keep coming.

“Two men got air dropped right into the middle of a German bivouac. They saw the parachutes coming in and caught them with radios and everything,” Cardinalli said.

The two were separated and interrogated. When one of the agents was eventually recovered, he was missing half of an ear – a botched attempt to try to pry information out of him. His teammate had been executed.

Nazi officers began using the captured radio to try to secure information from Allied forces. But without the coded signal “didit, didit,” Cardinalli and his team knew something was up.

But the code was hardly needed.

“When an operator transmits, I can tell who’s sending – just like a person’s voice,” he said.

The war in Europe was ending, and Cardinalli returned to Washington. It wasn’t long before orders came that he would be sent to the China-Burma-India arena, an assignment he strenuously objected to.

“I said bull—-. I signed in and I’m signing out. I want out,” he said. Instead, he got a 45-day furlough that was subsequently extended and extended again.

Finally, he was re-assigned to Washington. Then a staff sergeant, Cardinalli was placed in charge of documents and files to be submitted as evidence in the Nuremberg war crimes trials. With the death of Franklin Roosevelt, Harry Truman became president, and the OSS was reorganized as the CIA.

Soon after, Cardinalli came home. He worked a commercial fishing boat in Alaska for 20 years, became a painting contractor, built much of the Sunnyslope area of Hollister with his partners and friends and was one of the founders of San Benito Bank.

Through it all, there were the memories, memories that the war, then the Cold War, required he keep under wraps.

As those events fade into history, Cardinalli can now talk about his past, a past in which he takes justifiable pride.

“The OSS saved thousands and thousands of lives,” he said.