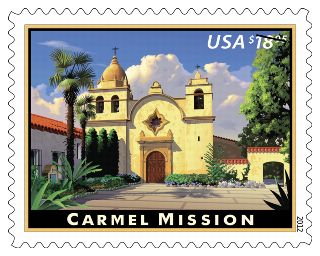

When sightseers tour the centuries-old Spanish mission tucked off Highway 1 in Carmel-by-the-Sea, it’s likely they’ll admire the red-tiled roofs, the chapel’s aesthetic facade, the prominent dome bell tower, the exquisite gardens or the vast collection of liturgical art.

For Louise Ramirez – a former Gilroy resident and Tribal Chairwoman of the Monterey-indigenous Ohlone Costanoan Esselen Nation – the landscape is far from romantic.

Her gaze drifts to the right of the sanctuary, where an adobe archway and wrought iron gate mark the portal to a mass grave filled with thousands of Ramirez’s ancestors. Most are buried in unmarked sites; more remains have been found scattered about the property.

“The missions were our jails. They were where our people were enslaved, murdered, stuffed in the walls as insulation, tortured and raped,” Ramirez, 61, said.

The cemetery archway is the first thing Ramirez, who now lives in San Jose, sees when she studies the Carmel Mission Express Mail stamp recently unveiled by the U.S. Postal Service.

Created in “honor of nearly 250 years of California history,” the design is one of 20 to 25 stamps seen to fruition each year out of an average 50,000 ideas submitted to the U.S. Postal Service annually.

A special ceremony commemorating the stamp’s first day of issue took place today at the historic Roman Catholic mission built in 1771, located 45 miles southwest of Gilroy where it overlooks the ocean in Monterey County. It served as headquarters for Father Junipero Serra, who was buried beneath the chapel’s floor when he died in 1784. Today, the Carmel Mission has been designated a National Historic Landmark and is an active parish of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Monterey.

Citing “discomfort and concern with the unveiling of the stamp” in a Feb. 16 letter addressed to U.S. Postmaster General Patrick Donahue, Ramirez isn’t the only one who feels the mission is undeserving of a positive limelight. Her concerns are echoed by Valentin Lopez, 60, chairman of the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band.

While the Mutsun tribe is principally associated with Mission San Juan Bautista and the surrounding areas of Gilroy and Hollister, Lopez explains the Carmel Mission, “like the other Franciscan missions in California, was actively involved with the massacre and genocide of California Indians.”

In a Feb. 8 letter to Postmaster Donahue, Lopez underlines the attempted, and in many cases successful, eradication of Native American languages, religious beliefs, social, political, ecological and cultural practices.

“That the federal government can even contemplate commemorating such an institution … is especially offensive to those whose ancestors were subjected to the harsh conditions of Mission Carmel,” wrote Lopez, who lives near Sacramento.

On behalf of the Mutsun, Lopez requested in his letter that the stamp not be released, and that “no honor be accorded to Mission Carmel.”

As of Monday, Ramirez and Lopez said the postmaster had not responded to their letters. In attempts to contact Donahue, the Dispatch was referred to Augustine Ruiz, postal spokesman for the Bay Valley District who said the concerns expressed by Ruiz and Lopez are “perfectly understandable.”

However, the U.S. Postal Service has no plans to halt the stamp’s release, he said.

“I understand it; I can empathize with it,” he said. “Anytime anything is introduced, there’s some element of controversy that’s usually attached to it.”

Ruiz reached out to the OCEN tribe in preparing for today’s ceremony. As tribal spokeswoman, Ramirez was invited to offer a blessing and prayer for her ancestors, followed by a speech in remembrance of her people.

Despite some opposition from her fellow OCEN members – many are practicing Catholics and did not approve of Ramirez “speaking against the missions” – Ramirez still accepted.

“I’m going to try, and hopefully I can get (the audience) to understand what we’ve been through, and what the missions have done to us,” she said. “It’s important that people know that we’re here. And if we refuse to attend these things, they’re never going to know we were there.”

In this particular case, Ruiz explained the stamp is meant to commemorate the Carmel Mission (formally known as Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo) for its architectural beauty and iconic place in California’s roster of historic buildings. It is the second oldest of California’s 21 missions and is often described as the most beautiful, Ruiz said.

The focus on architecture is elaborated in a U.S. Postal Service press release, which highlights the stamp’s colorful illustration depicting the church’s attractive façade. An earlier announcement released by the U.S. Postal Service Feb. 21 describes the mission as a landmark in California’s Spanish heritage.

While considered a bastion of California’s architectural landscape, “Spanish heritage” resonates differently for present day Native Americans.

For individuals such as Ramirez and Lopez, the phrase evokes a bitter reality of life beneath the Spanish Catholic regime; a subservient existence indigenous peoples were subjected to when European colonization of the Pacific coast began in the 1770s.

Stories of Native American children being snatched from their villages (a tactic used to lure parents to the missions, Ramirez said) forced slave labor and the perpetual raping of young girls by Spanish guards weigh heavily on Ramirez’s mind when she thinks about ancestors, and what they faced more than two centuries ago.

Similarly, Lopez said celebrating the physical features and scenic virtues of Mission Carmel “while ignoring its brutal history” isn’t something the Mutsun take lightly.

“I’d like them to just stop the design and not do it,” said Lopez, referring to the stamp. “They shouldn’t be honoring this place.”

The U.S. Postal Service’s release of a stamp 26 years ago honoring Father Junipero Serra, who is buried in the chapel floor of Mission Carmel, was also source of outrage for Native Americans, Lopez noted.

“That’s why I was surprised to see this,” he said. “I thought they would have learned from (Serra’s) stamp.”

Ruiz acknowledged the U.S. Postal Office will never be able to make everyone happy when it comes to the development of new stamps. The selection process involves a citizen’s stamp advisory committee, which is made up of about 12 private citizens from “all walks of life” from around the country, Ramirez said.

“While it does have some controversy, we realize that and wanted to make sure that everyone was included in the ceremony,” said Ruiz, referring to today’s event. “That’s why I reached out to Louise.”

Assigned several times by the California Native American Heritage Commission as the “most likely descendant” when it comes to reburying ancestral remains that have been disturbed at the Mission Carmel cemetery, Ruiz’s genealogy traces all the way back to 1717 to a woman named Leonila Maria. This distant relative once lived in the Echilat village in the Santa Lucia mountains.

Originally from Salinas, Ruiz lived in Gilroy for seven years beginning in 1965. She married Ernest Ramirez in 1972, a 64-year-old Gilroy native and a cousin of City Councilman Peter Arellano.

Going forward, both the OCEN and Mutsun have expressed interest in proposing stamp designs in honor of their Native American ancestors; something Ramirez told the Dispatch the U.S. Postal Service would be “more than happy to entertain.”

Lopez recommend in his letter a stamp be issued in honored of Ascencion Solorzano, a Mutsun tribal ancestor for whom Ascencion Solorzano Middle School in Gilroy is named after.

Above all, honoring her heritage through education and outreach is Ramirez’s eternal objective.

“We’ve been in this situation before, and we feel that education is more important than not doing it,” said Ramirez, of her decision to speak at Mission Carmel today. “Nobody is going to know we’re here unless we take advantage of the opportunity to speak with the public.”