SBHS students asked ‘What kind of person are you going to

be?’

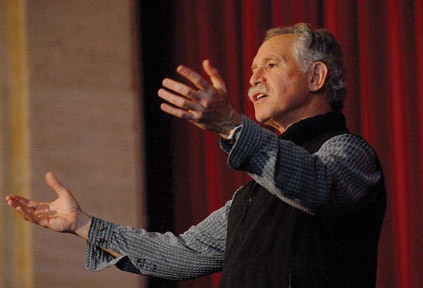

San Benito High School students gathered in the school’s

auditorium Feb. 28 and March 1 to listen to the powerful words of

Jerry Falek, a storyteller who uses just his voice to focus

students on an important question.

”

What kind of person are you going to be?

”

he asked.

It was a refrain he repeated throughout his presentation, which

filled most of the class period, with a little time leftover for

interaction with the students.

SBHS students asked ‘What kind of person are you going to be?’

San Benito High School students gathered in the school’s auditorium Feb. 28 and March 1 to listen to the powerful words of Jerry Falek, a storyteller who uses just his voice to focus students on an important question.

“What kind of person are you going to be?” he asked.

It was a refrain he repeated throughout his presentation, which filled most of the class period, with a little time leftover for interaction with the students.

Tom Rooth, an English teacher, invited Falek to speak again this year to share his family’s experience with the Holocaust. The presentation was funded in part by Community Foundation for San Benito County and the Baler Foundation. Executive director Gary Byrne and two other staff members attended an afternoon performance of the show.

“You have a very special opportunity today,” Rooth said, as he introduced the storyteller. “Jerry Falek is a friend and colleague, a talented artist. He is an expert in conflict resolution for which he travels around the world.”

As he asked the students to put away cell phones and listen to the guest, he talked a bit about the art of storytelling.

“Storytelling used to be the way people transmitted culture from one generation to another,” Rooth said.

Falek’s presentation followed closely the performance he gave to students last year. He started out by saying there is only one question people have to answer in life, but that the answer might be different when they are in their teens, when they are in their 20s, when they are in their 50s and 70s.

“The answer might be different on Friday than on a Tuesday,” he said. “The question is what kind of person are you going to be – a person who sticks up for friends, or those in your community, or those in your region or even those outside your region? Are you going to be a person who sticks up for people or puts people down?”

Falek gave a brief history of the Holocaust – that between 1942 and 1945, six million Jewish people were killed. But he added more than five million other people were also killed – political dissidents, gays and lesbians, gypsies and people with physical disabilities.

With that, Falek launched into his first story about how his mother came to America, told from the point of view of his grandfather. The students in the audience listened quietly as Falek took on the mannerisms of a grandfather with a strong German accent. His grandfather had fought for Germany in World War I. He had lost two brothers. His family had a history in the country that dated back 500 years. He owned a building supply store in town. He had a family, including his oldest daughter, Ruth, Falek’s own mother. He talked about how strong Ruth was as a baby, even when she was sick. A doctor had almost given up on her, when the toddler stood up in her crib and started bouncing up and down to show there was still life left in her.

As a teenager, when the Nazis started to come into town and rumors started that Jews were in danger, Ruth’s father refused to leave the country. Ruth, however, decided to leave when she was 17 for America, where she had no family. She settled in New York, got married and had children. But in 1942, letters from her family overseas stopped arriving. Her entire family was lost in the concentration camps.

Falek’s second story told a tale of Simon Wiesenthal, an activist who fought to bring Nazi war criminals to justice following the end of the war. Wiesenthal was taken into the concentration camps when he was 30. As an able-bodied man, he was sent out on different assignments as a slave laborer.

For one of his assignments, he was taken to the town where he had attended college. He was taken into one of the buildings of the old college, now being used as a hospital for injured Nazi soldiers. There he was assigned to listen to a dying soldier. The soldier said he had done a terrible thing and he needed a Jew to listen to him, and forgive him, before he could die in peace.

The 21-year-old soldier talked about how he was recruited for the Hitler youth when he was 12 years old. The boys were told they would be the glory of Germany. They were taken on hiking trips, taught to shoot guns and told that Jewish people were the reason for all the problems in the country. Wiesenthal listened to the soldier talk about all the things he was forced to do, as a Hitler youth, and later when he joined the Special Forces. He talked of burning a group of people alive when he and other soldiers threw grenades into a building in which they were trapped.

Falek ended the story without saying whether Wiesenthal was able to forgive the soldier.

“In conflict war, there are five roles,” Falek said. “There are the aggressors, or Nazis in this case. There are the victims, the person to whom things happen. My grandfather was a victim. There are the resisters who fight against it. There are the rescuers who help others, and put themselves in danger. And there are bystanders, people who do nothing and let those things happen.”

He said the reason he tells the stories is to remind people of how important it is to stay involved.

“I would love to think I would have the courage to do something, but I don’t know,” he said. “We can start with finding courage in our own life and community.”

At the end of his presentation, while some teachers had their students return to their classes, Falek asked the remaining students to share if they would have forgiven the Nazi soldier. The students were split about 50-50.

One of the students said he would have forgiven the soldier, but he didn’t know why. Another said the soldier realized what he did wrong so he should be forgiven. Another said he knew what he was doing was wrong all along so he shouldn’t be forgiven.

“Remember there are no wrong or right answers,” Falek said. “And your answer might change at different times in your life.”