On March 31 each year, Californians celebrate the life and legacy of a man who brought hope, courage and justice to those who labor in the agricultural fields of America. César Chávez (March 31, 1927–April 23, 1993) advocated for fair treatment, wages and working conditions of farm workers in countless of communities across the country.

In San Benito County, Chávez is remembered by many, but none quite like the farm workers who shared some of the most challenging, but rewarding times with the legendary labor leader.

This historic account begins in 1977 in San Benito County. A time not much different than it is today—a tranquil setting surrounded by fertile lands as far as the eye can see. That tranquility came to a necessary standstill that would take its place in American history.

That year, hundreds of farm workers voted for union representation at Bertuccio Farms. Farm workers had grown tired of the low wages, unfair treatment and substandard working conditions. At that time, Bertuccio Farms was the largest agricultural employer in San Benito County— harvesting lettuce, onion and apricots.

Farm workers felt a sense of hopelessness, but their solidarity did not succumb to their circumstances, as they had heard of a soft-spoken leader with a powerful voice dedicated to fighting for the rights of farm worker. A man who in 1967 had successfully negotiated a contract for farm workers with former San Benito County Paicines wine giant Almaden. The workers plight was soon heard throughout the California Central Valley in Delano by labor leader César Chávez.

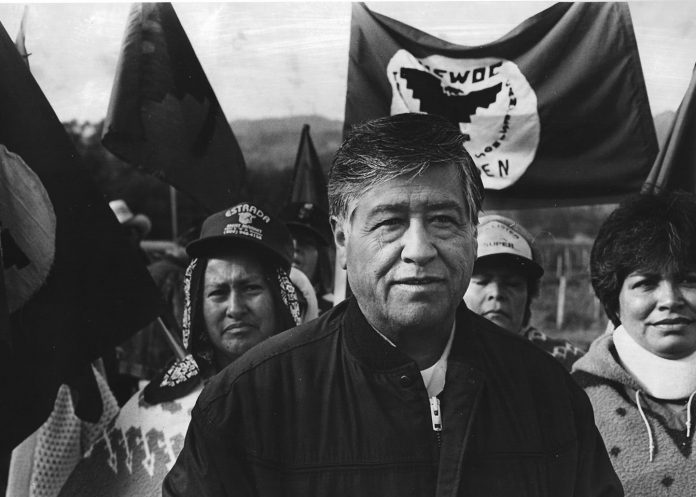

That summer, César Chávez, his youngest son Paul Chávez and the United Farm Workers (UFW) union had arrived in San Benito County to renew the farm workers right to unionize. Paul Chávez served as director of the Hollister UFW Field Office located on East Street. Paul Chávez, now chairman of the César Chávez Foundation, remembers that Hollister gave him his first experience as labor organizer of farm workers.

For over three years, the UFW continued contract negotiations with Bertuccio Farms, but the Bertuccio family held firm. The atmosphere in Hollister coiled in tension and workers had made the tough decision to go on strike. The morning of July 9, 1981 began with a distressing cry “Huelga, Huelga, Huelga!” (Strike, Strike, Strike!) a word that would come to define an entire movement of farm workers. Hundreds of Bertuccio Farm workers walked out of the fields firmly grasping the UFW flag, a red and black symbol depicting an Aztec eagle representing courage and dignity. In fact, courage would be needed as strikes were not taken lightly. This decision meant that hundreds farm workers would have to go without pay.

“Those were difficult times for our family, my children had to often go without the basic necessities. Nevertheless, that experience brought our family closer,” said Hollister resident Jose Carmen Lezama, past Bertuccio Farms employee and UFW picket line captain.

Farm workers knew that sacrifice was unavoidable.

“The strike lasted for a year and we were fighting for more than our jobs, we were fighting for our dignity,” said Javier Ceja, Hollister resident and past employee of Bertuccio Farms and UFW strike captain.

On Aug. 7, 1981, San Benito County made national news. Every major news media outlet across the country, reported that César Chávez, his son Paul and 30 Bertuccio Farm workers, including local residents Lezama, Ceja and Perez had been placed under arrest by San Benito County Sherriff’s deputies for trespassing while challenging the union’s right to organize workers.

Following the arrests, a local judge placed a temporary restraining order on the UFW— restricting the union’s access to non-strikers on Bertuccio Farms property. At that time, the California Supreme Court was considering a ruling on union access to employer properties to talk to non-strike members. However, this setback did not slow down the strike. A few days after being released, the Chávezs and 34 workers challenged the access ruling by the San Benito Superior Court and had faced the same result. After much deliberation, the court granted the UFW limited access to Bertuccio Farms’ property. This was a win for the UFW because this allowed union members to talk to non-striking workers during their one-hour lunch and breaks.

Over the next several months, contract negations continued without success.

By then, the strike had ripened and workers had learned to organize. Hollister farm workers began a boycott of Bertuccio Farm products—traveling daily to South San Francisco and Oakland. On occasion workers traveled as far as Los Angeles. Farm workers began to put pressure on owners of markets and warehouses to see if they would remove Bertuccio Farm products from their place of business; if the owners refused, the workers would picket.

“In the union I learned to speak English, I also learned something that you do not learn in school and that is to defend your rights,” said Hollister’s Ramiro Perez, past employee of Bertuccio Farms and UFW contract negotiations committee president.

In 1982, the California Agricultural Labor Relations Board charged Bertuccio Farms with “bad-faith bargaining.” By that time, most of Bertuccio’s 3,000 acres were empty; as 350 of the 400 workers had joined the strike. The Bertuccio family was constrained to picking the fields or risk losing millions of dollars in revenue.

Bertuccio Farms never signed a contract with the UFW. However, the farm worker experience in San Benito County began to change. Farm workers started to see better treatment, wages and working conditions.

The Bertuccio Farms effort would demonstrate to be one of the last glimpses of César Chávez as an organizer of farm workers. However, the Chávezs continued to work in San Benito County by organizing countless marches, bringing national attention to the dangers of pesticides on consumers and farm workers.

Their “Si Se Puede” (Yes we Can) chants continue to resonate in the hearts of many San Benito County residents.