Former A’s slugger also acknowledged he bought HGH while playing

for Oakland, but said he threw the drugs away without using

them

WASHINGTON

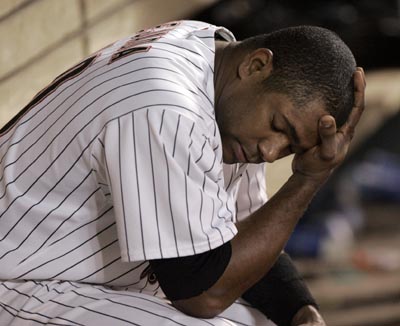

Dressed in a defendant’s dark suit instead of an All-Star’s crisp uniform, Miguel Tejada became the first high-profile player convicted of a crime stemming from baseball’s steroids era, pleading guilty Wednesday in federal court to misleading Congress about the use of performance-enhancing drugs.

Under a plea agreement with the same prosecutors pursuing a perjury indictment against Roger Clemens, Tejada admitted he withheld information about an ex-teammate’s use of steroids and human growth hormone when questioned by a House committee’s investigators in August 2005.

Tejada – the 2002 American League MVP with the Oakland Athletics and a five-time All-Star shortstop now with the Houston Astros – also acknowledged he bought HGH while playing for the A’s, but said he threw the drugs away without using them. Prosecutors said they have no evidence to contradict that.

The misdemeanor can lead to as much as a year in jail. Federal guidelines call for a lighter sentence, and it is possible Tejada will receive probation only. Federal Magistrate Judge Alan Kay set sentencing for March 26. That’s during spring training, but the Astros are not scheduled to play an exhibition game that day.

Kay asked more than once whether the Dominican Republic-born Tejada understood this could affect his immigration status in the United States. “Yes, your honor,” Tejada replied.A letter sent by prosecutors to his attorneys on Feb. 5 outlining the terms of their plea deal said: “His guilty plea in this case may subject him to detention, deportation and other sanctions at the direction of the United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement.”

An agency spokeswoman declined to discuss Tejada’s status and said cases of legal permanent residents convicted of a crime are reviewed individually to determine if deportation is appropriate.

Two immigration lawyers, Cleveland-based David Leopold and Maryland-based Laura Kelsey Rhodes, said Wednesday they would advise a client in Tejada’s situation not to leave the country until it’s clear he cannot be deported for this offense.

As with the pending cases against seven-time Cy Young Award winner Clemens and seven-time MVP and home-run king Barry Bonds – whose trial begins March 2 in San Francisco – Tejada got in trouble not so much for what he did, but what he said.

Tejada’s appearance came two days after his AL MVP successor, Alex Rodriguez, said he took banned substances while playing for the Texas Rangers in 2001-03. That admission came in the aftermath of a Sports Illustrated report that Rodriguez failed a drug test in 2003; he does not face criminal charges.

Even after being chastised by Kay for merely nodding in response to questions, Tejada did not say much in Washington on Wednesday other than “Yes, your honor” or “No, your honor” during the 45-minute hearing.

Tejada, his two lawyers and his baseball agent did not take questions from reporters on their way in or out of the courthouse. They planned a news conference later in the day at the Astros’ stadium in Houston.

The Astros did not comment after the hearing. But the Athletics issued a statement saying: “The Oakland A’s are saddened to learn of Miguel’s admission. We are fully supportive of Major League Baseball’s current policies and its ongoing efforts to eliminate banned substances from the game.”

When he entered the courtroom for what would be announced as “The United States of America vs. Miguel O. Tejada,” the player sat at the defendant’s wooden table with his lawyers, swiveling in his black chair, fiddling with the knot of his black-and-gray striped tie, and wiping sweat from his forehead and nose with his left hand.

Eventually – wearing headphones so he could hear a simultaneous translation into Spanish – Tejada rose and stepped forward to a podium, facing Kay, and was sworn in. He stated his full name, “Miguel Odalis Tejada Martinez.” Later, Tejada was asked how far he went in school and answered, “Eighth grade, sir.”

When the judge asked Tejada whether he had taken any medicine, drugs or alcohol, legal or illegal, in the previous 24 hours that could affect his decision, Tejada answered softly, “Um, last night, I took a couple of drinks.” But he told the judge he wasn’t under the influence of alcohol or drugs.

Toward the end of the proceedings, when Tejada was asked how he wished to plea, his voice cracked as he replied: “Guilty.” One of his lawyers patted him on the shoulder.

The case grew out of the March 17, 2005, congressional hearings on steroids in baseball at which Mark McGwire refused “to talk about the past,” and Rafael Palmeiro – Tejada’s teammate with the Baltimore Orioles – jutted a finger at lawmakers and denied taking steroids.

Palmeiro was suspended by baseball later that year after failing a drug test. That House panel looked into whether Palmeiro should be investigated for perjury; he said the positive test must have been caused by a tainted B-12 vitamin injection given to him by Tejada.

That led investigators to Tejada, who was questioned at a Baltimore hotel. He was not under oath, but court documents say he was advised “of the importance of providing truthful answers.”

During that interview, Tejada told congressional staff “he had no knowledge of other players using or even talking about steroids or other banned substances,” court documents say.

But in the December 2007 Mitchell Report on drugs in baseball, Oakland outfielder Adam Piatt is cited saying he discussed steroid use with Tejada and provided Tejada with testosterone and HGH. The report included copies of checks allegedly written by Tejada to Piatt in March 2003 for $3,100 and $3,200.

Congress decided not to ask the Justice Department to pursue charges against Palmeiro. But in January 2008, lawmakers referred Tejada to DOJ, a little more than a year before they asked that Clemens be investigated.

Before Tejada was allowed to leave the courtroom Wednesday, he was handed forms outlining the conditions of his release – weekly phone calls to check in, a standard drug test – and told to sign them. A man accustomed to putting his name on so many bats and balls forced to provide an autograph of a different sort.

–

Story by Howard Fendrich and Nedra Pickler, Associated Press Writers. Associated Press Writer Eileen Sullivan contributed to this report.