When it comes to history, I’m always entertained by uncovering the surprising chain of connections that link the past with the present. To illustrate this game of connect the historic dots, let’s take this year’s centennial celebration of Silicon Valley’s Villa Montalvo estate and connect it, along a winding avenue, to the reign of the great Holy Roman Emperor Charlemagne.

Villa Montalvo was built between 1912 and 1914 by U.S. Senator James Phelan in the foothills of Saratoga. Phelan, a figure we might today regard as California’s original Renaissance man, put in his will that the property would serve as a public park and cultural center for the “development of art, literature, music and architecture.” He named the estate after Garci Rodriguez de Montalvo, a popular Spanish novelist of the 16th century.

One of Montalvo’s most popular works was a chivalric fantasy story, written around the year 1500, titled “Las Sergas de Esplandian” (“The Adventures of Esplandian”). It features an island populated by women who fly around on griffins, the magnificent winged creatures of ancient myth. In honor of the novel, Phelan’s Villa Montalvo features stone sculptures of griffins set around its gardens.

The ruler of the island in Montalvo’s romance novel is a queen named Calafia, a pagan black woman. The name of the island she rules is California, the Latinized version of “land of Calafia.” At one point in the story, Calafia leads her army of women warriors and griffins to join Muslims in fighting the Christians, led by Esplandian, in conquering the Byzantine city of Constantinople. In the battle, Esplandian takes Calafia prisoner. She converts to Christianity and marries his cousin and returns to her island home.

Spanish conquistador Hernan Cortes was familiar with Montalvo’s novel. After he had conquered the Aztecs of Mexico, Cortes sent an expedition on a voyage to search for this mysterious island which, according to Montalvo, was located “on the right hand of the Indies” and blessed with gold and pearls. The explorers found what they believed to be an immense island west of Mexico. Above soared flying animals with wings spanning 10 feet that they believed to be the griffins of Montalvo’s novel. Naturally, they called the new land California.

Later expeditions found that the “island” was really the peninsula of Baja California. The name California, however, stuck to describe not just the peninsula but also the coastal territory north of it. As for the “griffins,” well, they turned out to be a native species of vultures known as California condors.

The roots of Montalvo’s novel about Esplandian’s conquest of Calafia go back to an 11th century French poem called “La Chanson de Roland” (“The Song of Roland”). In this epic, the knight Roland fights an Islamic army intent on conquering Christian Europe. In a battle set in the Pyrenees, Roland is killed by the infidel invaders. The poem refers to a mysterious land called Califerne, the homeland of the Muslim fighters. Literary theory proposes Califerne derives from the Arabic word “khalifa,” which refers to the leader of an Islamic community, and is translated to “caliph” in English and “califa” in Spanish. So, in a round-about side-trip through the Middle Ages, the name of the state of California can translate to mean “the domain of the caliphs.”

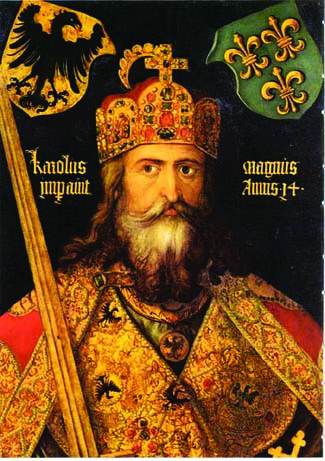

“The Song of Roland” is a heavily fictionalized account of on an actual battle that occurred in the Roncevaux Pass in the Pyrenees on Aug. 15, 778. A knight named Roland did fight and die in that battle. He was the nephew of the Frankish king Carolus Magnus, known as Charlemagne, who reigned over the Holy Roman Empire (now France and Germany) between 768 and 814. These years of rule are called the Carolingian Renaissance for the culture and scholarship that Emperor Charlemagne inspired. For example, Charlemagne ordered clerics to copy on parchment the comedies of the ancient Roman playwrights Plautus and Terence, preserving them for the ages – and providing a blueprint for Shakespeare’s comedies as well as today’s sitcoms. Another innovation that came out of the Carolingian Renaissance is the use of “minuscule” script in documents. Minuscule was a calligraphic script style that was much easier to read than previous medieval script. It led to the type fonts we use today, including the font you’re reading now.

I hope you enjoyed playing my game of six degrees of historic separation between Senator Phelan and Emperor Charlemagne. These two political leaders, both known for cultural and literary endeavors, are linked through the inspiration that novelist Montalvo found in a French epic poem about a knight named Roland.