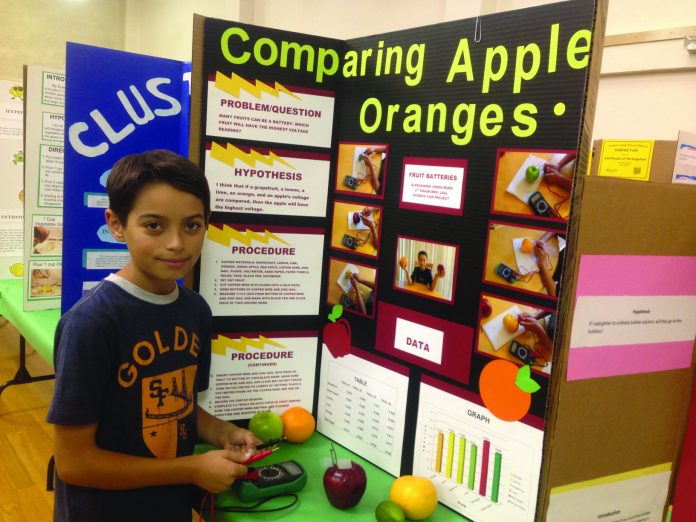

Alekzander Cress-Muro, 9, wants to be a paleontologist. The fourth grader at Tres Pinos School made apples, oranges and lemons into batteries last month using nails and copper wire. He hypothesized that apples would carry the most current and he used the scientific method to test his thoughts as part of his project for the San Benito County Science Fair.

“His teacher was like, ‘This project was a little more complex than it needs to be,’” said the student’s mom, Jennifer Cress, 40.

The science fair held March 24 brought in more than 170 student participants, but administrators at various levels are not sure science is taught enough in schools and have conflicting views on whether the state’s new Common Core standards encourage or discourage the topic.

“I do know they’ve come in and they’ve done very few labs, if any,” said Charlene McKowen, the principal of Anzar High School, as she reflected on incoming students’ experiences with the subject.

Since Anzar’s feeder schools are K-8 sites, the elementary school teachers have multiple-subject teaching credentials, instead of more specialized single-subject designations showing deeper mastery of one academic area, which instructors need to teach at middle or high schools, McKowen said. The amount of science students have experienced often depends on their elementary teachers’ comfort with the subject.

“It’s kind of a hybrid what we get,” McKowen said.

These words come from a principal in the Aromas-San Juan Unified School District, located just a 45-minute drive from San Jose, a city in the heart of Silicon Valley’s world-class innovation.

Nationwide, 58 percent of those surveyed by the Pew Research Center in a 2014 study selected science as one of the “most important” skills for children to get ahead in the world today. That number compares with a high of 90 percent who listed communication as an important skill and a low of 23 percent who listed art as a critical asset.

At Anzar High School, students complete a two-year program of University of California-approved integrated science courses that mix biology, life and earth science. Then, students can go on to take chemistry, advanced biology or physics.

Students make presentations about science and other topics during exhibitions—complex, issue-based projects that include a research paper and oral presentation—which are required for graduation.

“The exhibition does sort of showcase that they know how to think scientifically, whether or not the issue they’ve chosen has anything to do with what they’ve studied,” McKowen said.

Veronica Canales, 31, attended the county science fair last week with her daughter Jasmine, who created a poster on the golden ratio for beauty as a requirement for her class at Calaveras School in Hollister. Canales remembers taking on regular science projects when she was in school, but this was her daughter’s first project this year. Canales’ daughter, who will be in eighth grade next year, carried out a project that evaluated how pop stars such as Christina Aguilera, Miley Cyrus and Mariah Carey compare to a mathematical formula for beauty.

“I think they could use more science at school,” she said. “When I was growing up, we did a project probably every week.”

Accelerated Achievement Academy Principal Joe Rivas noted his students get a dose of science every school day while the ones at Calaveras School, where he is the assistant principal, get science three to five times a week depending on the teacher.

At the academy—which shares a campus with Calaveras—Rivas is working to get teachers a membership to the Resource Area for Teaching, or RAFT, where he says instructors with “the right creative eye and mind” can find great science materials.

Rivas, a former science teacher, believes the subject area fits well with the state’s new Common Core standards because it is mostly nonfiction reading.

“Science, I almost feel like, is being used more in the classroom (now) because of the text it has,” he said. “It’s not really about stories anymore. It’s about informational reading and informational text.”

Sunnyslope School Principal Bill Sachau watched his son, William, who attends Cerra Vista School, participate in the science fair this year. The youth took home a first-place trophy for a project that questioned whether changing the color of a baseball would affect a batter’s ability to hit it.

Sachau saw the excitement on his son’s face when he won and said he wants to bring science fair projects to his own campus next year. Sunnyslope also has a new assistant principal with a strong science background who wants to see the school become competitive next year, he said.

Sachau emphasizes that administrators will need to provide teachers with support so that science is not just another thing to do.

As for how teaching science was affected by Common Core, Sachau doesn’t see a strong emphasis on the subject from the state yet.

“It’s not a really big part of Common Core,” he said. “They’re still working on it, but it’s coming .”

Currently, math and language arts skills are tested in the state’s new standardized tests for younger students, but there is no science component to the exam, he said. Older students take a separate science test for the state based on the fourth and fifth grade standards, he said.

At the science fair, fourth grader scientist-in-training Alekzander Cress-Muro adjusted his apple battery and prepared to check the electrical current with a voltmeter.

“It was really great,” said his mother. “It got him really interested in science, which he wasn’t that interested in at first.”