It’s not every day you ride around with a famed California wine historian and best-selling author while he runs errands. But I had the chance to sit in Charles Sullivan’s maroon Lexus (with a license plate that reads: ZINFDL) and chat with him about local wine history as we drove around Santa Clara.

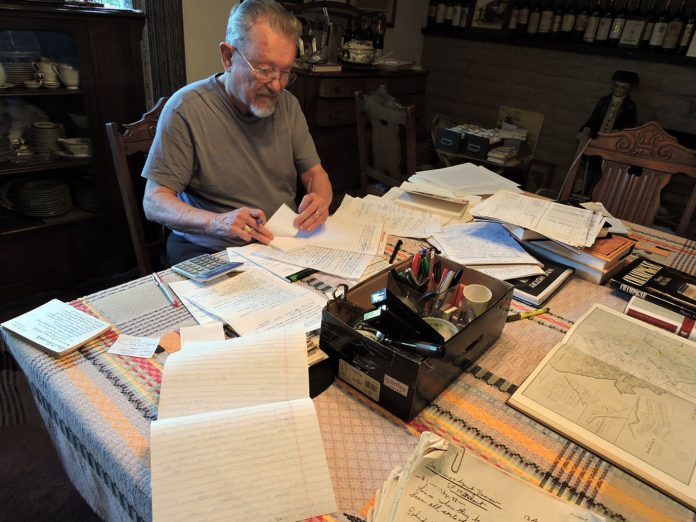

Sullivan has spent decades investigating wine in California, writing more than 100 articles and authoring several books that bring to life a comprehensive history of the world of wine from long ago.

As we drove around town he recited facts and pointed out old winery locations most would never know existed—but he wasn’t always interested in wine. In college he didn’t drink wine but, when he came back from the Korean War in 1957, he returned to graduate school at UC Berkeley.

“Near where we lived in Berkeley there was a liquor store and we started drinking champagne for $1 a bottle—Korbel,” Sullivan said. “That was in the late ’50s. Then we moved down here (Campbell) and we started buying jugs and soon we were drinking wine with dinner every night.”

Sullivan would buy jug wine from local wineries Guglielmo and Pedrizzetti (now Morgan Hill Cellars).

“Jug wines were the way to go if you were young and watching your dollars. Cork wine was for special occasions—now it’s all corked wine,” he said. “But let me tell you, there were some really good jug wines.”

In 1976, Sullivan had two friends over for dinner and one said, “Charles, all you do is talk about history—isn’t there something you can do?” Sullivan responded, “Well, historians answer questions—that’s what we do.” His friend quickly replied, “What’s a mystery you could solve?” “Well, the mystery of Zinfandel,” Sullivan said. “Nobody really knows.”

Sullivan was a high school history teacher at the time but the idea intrigued him.

“So, they talked me into a study of Zinfandel,” he said. “There was no really good history so I started collecting materials—just sort of as a hobby.”

He studied old records, catalogues and articles and with this historical evidence he was able to piece together the history of Zinfandel.

“Zin probably was a cross between two related vines in an area of the old Austrian Empire, then part of the Kingdom of Hungary, which was all part of the empire, and which is today within the Croatian Republic,” Sullivan said, noting an article he wrote that was published in the Journal of the California Historical Society in 1978. “I wrote this article and it made me famous. I became a wine historian.”

When looking at the history of Santa Clara Valley wines, this area has been considered wine country since the earliest mission days. But what helped put it on the map were quality wineries established after 1850.

In Santa Clara Valley, “the flatland became prunes and apricots after the 1870s,” Sullivan said. But by the 1880s, there were 13,000 acres of vines. “As of about 1890, so far as quality was concerned, Napa was the leader, Livermore was second and Santa Clara Valley was third. This was because there were a lot of really fine wineries in the Cupertino area and Mountain View and Evergreen area.” During that time, Sullivan added, “Paul Mason (now known as the Mountain Winery), Mirassou Winery and Almaden Winery were all considered premium wine in this area.”

“And then by 1900 there were only 6,000 acres that survived after the phylloxera outbreak,” Sullivan said. Phylloxera was a yellow insect, measuring no larger than 1/25th of an inch long, which was believed to come to California in the late 1880s from cuttings brought over from Europe. Phylloxera destroyed roughly 50,000 acres of vines in California.

In 1920, Prohibition began, bringing another hit to the wine industry. At the start of Prohibition, Santa Clara County had roughly 8,000 acres of vines and even though selling wine was prohibited, wineries were still able to sell grapes.

“You have all these vineyards around that are selling their grapes for home winemakers,” Sullivan said. “A lot of those grapes came from Santa Clara Valley,” Charles said.

Looking at today’s vineyards, the big threat seems to be available acreage and the loss of current vineyards to urbanization. Today there are only about 1,400 acres of vines growing in Santa Clara Valley and that number could continue to decrease.

In Napa County there is a zoning ordinance in place to protect the future of vineyards so developers can’t come in and tear them out in order to build shopping centers or housing developments. No such zoning ordinance exists in Santa Clara Valley.

“The tendency is for the Valley to get fewer and fewer grapes as it fills up more and more. I think the foothills and the mountains are the future,” Sullivan said. “The greatest concentration of vines today in Santa Clara Valley is in the foothills and the Santa Cruz Mountains.”

Vineyards have to be at least 400 feet in elevation to be considered in the Santa Cruz Mountains, according to American Viticultural Area (AVA) guidelines. If the vineyard is below 400 feet, it’s in the valley.

“It’s interesting to note that the valley wines haven’t been disappearing so much but they’re rare,” Sullivan said.

Santa Clara Valley wines may be rare, but hopefully they’re here to stay.

Chrissy Bryant is a Morgan Hill native. This article is part of a series to complete a master’s degree project at San Jose State University.